Point Charge: Difference between revisions

Mrandall34 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Claimed by | Claimed by Gabriel Cruz Fall 2025 | ||

This page is all about the [[Electric Field]] due to a Point Charge. | This page is all about the [[Electric Field]] due to a Point Charge. | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

(Ch 13.1 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | (Ch 13.1 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | ||

'''Point Charge/Particle''' | '''Point Charge / Particle''' — an object whose radius is extremely small compared to the distances to other objects in the system. Because it is so small, all of its charge and mass can be treated as if they are concentrated at a single point. | ||

* Electrons and protons are always treated as point particles unless stated otherwise. | |||

*Electrons | |||

<u>Two types of point charges:</u> | |||

* **Protons ( +e )** → positive point charges, <math>q = +1.6\times10^{-19}\text{ C}</math> | |||

* **Electrons ( –e )** → negative point charges, <math>q = -1.6\times10^{-19}\text{ C}</math> | |||

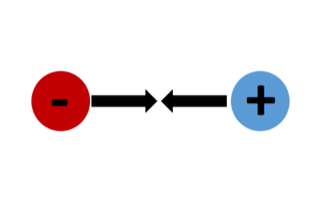

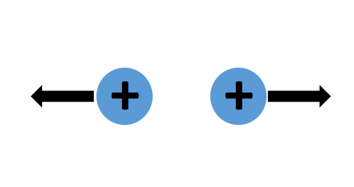

''Like'' point charges '' | ''Like'' point charges '''repel'''; ''opposite'' point charges '''attract'''. | ||

<th> Point Charges </th> | <table border> | ||

<th> Result </th> | <tr> | ||

<th>Diagram</th> | <th>Point Charges</th> | ||

<th>Result</th> | |||

<th>Diagram</th> | |||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td> 1 proton, 1 electron</td> | <td>1 proton, 1 electron</td> | ||

<td> Attract </td> | <td>Attract</td> | ||

<td>[[File:Proton_electron_attraction.png]]</td> | <td>[[File:Proton_electron_attraction.png]]</td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td>2 protons </td> | <td>2 protons</td> | ||

<td> Repel </td> | <td>Repel</td> | ||

<td>[[File:Proton_repulsion.png]]</td> | <td>[[File:Proton_repulsion.png]]</td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

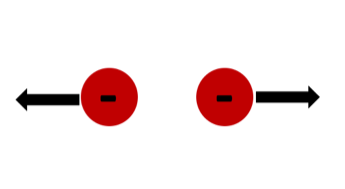

<td>2 electrons </td> | <td>2 electrons</td> | ||

<td> Repel </td> | <td>Repel</td> | ||

<td>[[File:Electron_repulsion.png]]</td> | <td>[[File:Electron_repulsion.png]]</td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table border> | </table border> | ||

===The Electric Field=== | ===The Electric Field=== | ||

(Ch 13.3 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | (Ch 13.3 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | ||

The electric field describes how a source charge influences the space around it. This field exists everywhere, even if no other charges are present to experience a force. The electric field allows interactions to occur at a distance. | |||

It is important to note that **electric field is not the same as electric force**. | |||

Electric Field | Electric Force due to an Electric Field: | ||

*F = | |||

*E = electric field at | <math>\vec{F} = q\vec{E}</math> | ||

*q = | |||

The | * **F** = force on the particle | ||

* **E** = electric field at the observation location | |||

* **q** = charge of the particle (assume <math>1.6\times10^{-19}\text{ C}</math> unless stated otherwise) | |||

The electric field becomes weaker as the distance from the point charge increases. | |||

<table border> | <table border> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

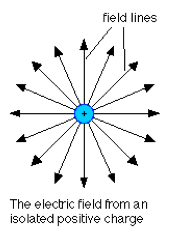

<td>The electric field of a positive point charge points radially outward</td> | <td>The electric field of a positive point charge points radially outward.</td> | ||

<td>The electric field of a negative point charge points radially inward</td> | <td>The electric field of a negative point charge points radially inward.</td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td>[[File:Proton_electric_field.png]] </td> | <td>[[File:Proton_electric_field.png]]</td> | ||

<td> [[File:Electron_electric_field.png]] </td> | <td>[[File:Electron_electric_field.png]]</td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table border> | </table border> | ||

===A Mathematical Model=== | ===A Mathematical Model=== | ||

====Electric Field | ====Electric Field Due to a Point Charge==== | ||

(Ch 13.4 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | (Ch 13.4 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | ||

The magnitude of the electric field decreases with increasing distance from the point charge. This is described by | The magnitude of the electric field decreases with increasing distance from the point charge. This is described by: | ||

<math>\vec{E} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q}{|\vec{r}|^2}\hat{r}</math> (Newtons/Coulomb) | |||

<math> | * <math>\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}</math> is Coulomb’s constant, approximately <math>8.987\times10^{9}\frac{N\,m^2}{C^2}</math> | ||

* **q** = charge of the source particle | |||

* **r** = distance from source location to observation location | |||

* <math>\hat{r}</math> = unit vector pointing from the source to the observation point | |||

'''Reminder:''' <math>\hat{r}</math> always points from the source charge to the observation location. | |||

The direction of the electric field depends on the sign of the source charge: | |||

* If the source charge is positive → field points away (same direction as <math>\hat{r}</math>) | |||

* If the source charge is negative → field points toward the charge (opposite <math>\hat{r}</math>) | |||

====Coulomb Force Law for Point Charges==== | ====Coulomb Force Law for Point Charges==== | ||

(Ch 13.2 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | (Ch 13.2 in ''Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood'') | ||

<math> | <math>|\vec{F}| = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{|Q_1 Q_2|}{r^2}</math> | ||

Coulomb’s Law describes the magnitude of the electric force between two point charges. | |||

The full vector form is: | |||

<math>\vec{F} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{Q_1 Q_2}{r^2}\hat{r}</math> | |||

* <math>Q_1, Q_2</math> = the charges | |||

<math> | * **r** = the distance between the two charges | ||

* <math>\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}</math> = Coulomb’s constant | |||

====Connection Between Electric Field and Force==== | ====Connection Between Electric Field and Force==== | ||

The force on a test charge is given by <math>F = Eq</math>. | |||

Substituting Coulomb’s Law for **F**: | |||

<math> E = \frac{F}{q_2} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q_1}{r^2}\hat{r} </math> | |||

The similarity of the Coulomb force law and electric field equation comes from the fact that the electric field is the force per unit test charge: | |||

<math>\vec{E} = \frac{\vec{F}}{q_{test}}</math> | |||

Direction rules: | |||

* If the source charge is positive → force and field point away from the charge | |||

* If the source charge is negative → force and field point toward the charge | |||

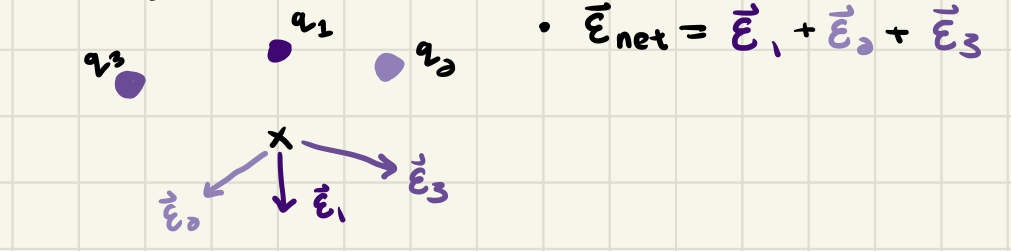

====Electric Field Superposition (Point Charges)==== | |||

When multiple point charges are present, the **net electric field** is the vector sum of the electric field from each charge: | |||

<math>\vec{E}_{net} = \sum \vec{E}_i</math> | |||

This is due to the principle of **superposition**: the total effect is the sum of individual effects. | |||

Important reminders: | |||

= | * A charge does not exert a force on itself | ||

* Source charges are assumed not to move (so <math>\vec{F}_{net} = 0</math>) | |||

[[File:IMG_1DCC0A11C7B8-1.jpeg]] | |||

===A Computational Model=== | |||

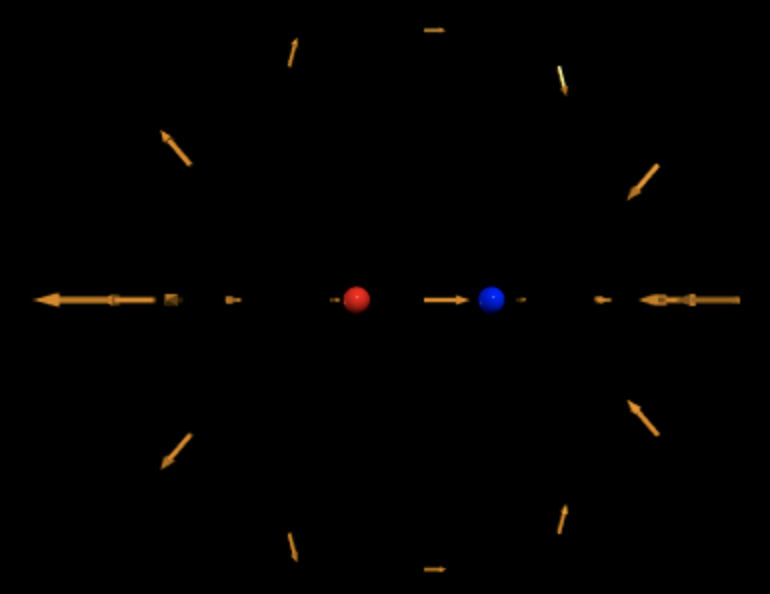

Below is a simulation showing the electric field at various observation locations around a proton. The arrows decrease in size according to <math>\frac{1}{r^{2}}</math>, showing how the electric field weakens with distance. | |||

[[File:First code.gif]] | |||

( | Two adjacent point charges of opposite sign form an electric dipole. The electric field points toward the negative charge (blue) and away from the positive charge (red). | ||

[[File:Code_2.png]] | |||

===A Computational Model 2 === | |||

[https://trinket.io/glowscript/650fbf3a95c5 Click this link to see another computional model.] | |||

==Examples== | |||

===Simple=== | |||

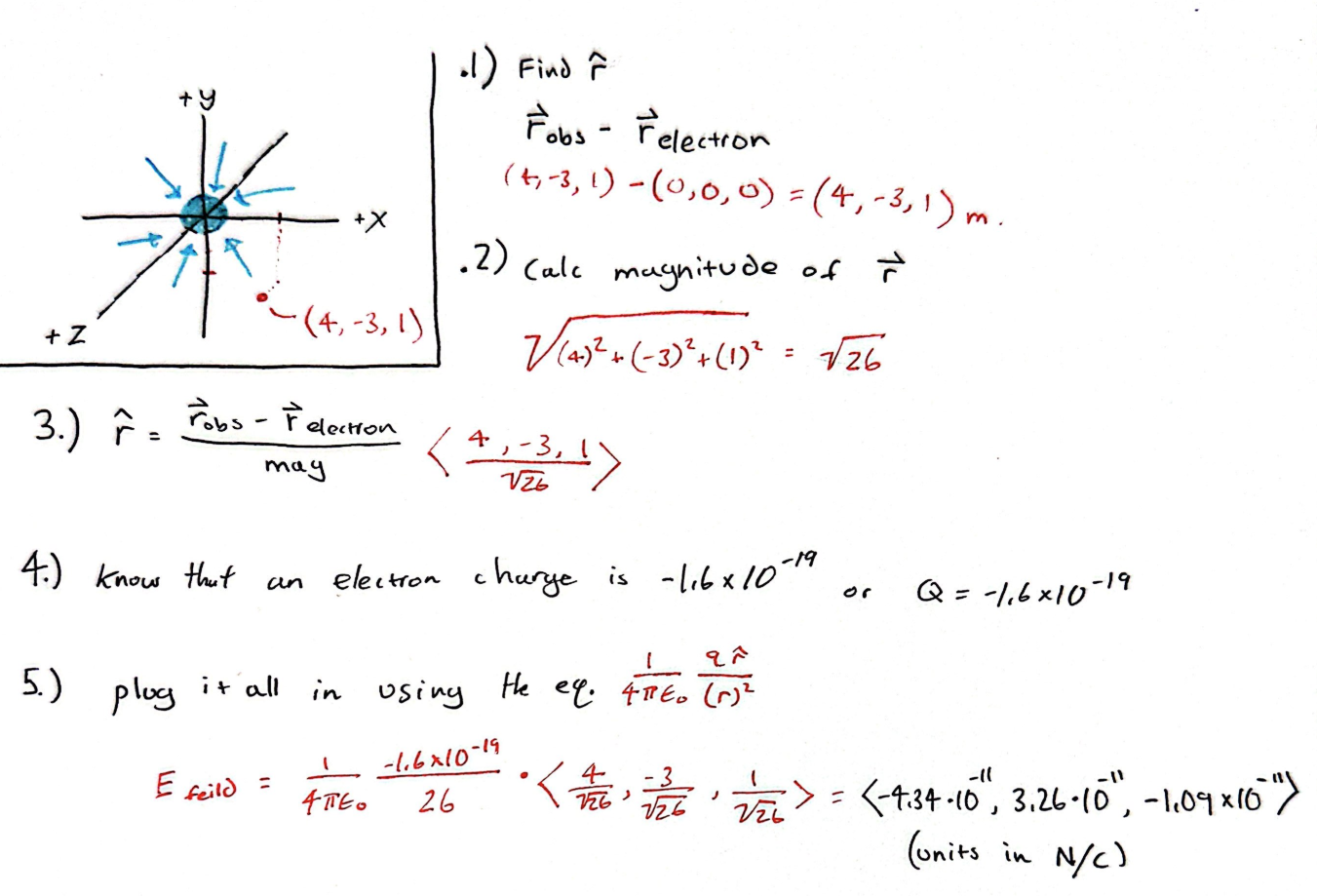

There is an electron at the origin. Calculate the electric field at <4, -3, 1> m. | |||

[[File:Screenshot_2024-04-13_160839.png]] | |||

===Middling=== | ===Middling=== | ||

| Line 183: | Line 200: | ||

===Difficult=== | ===Difficult=== | ||

The electric force on a - | The electric force on a -2 mC particle at location (3.98, 3.98, 3.98) m due to a particle at the origin is | ||

<math>\langle -5.5\times10^{3},\, -5.5\times10^{3},\, -5.5\times10^{3}\rangle</math> N. | |||

What is the charge on the particle at the origin? | |||

Given the force and charge | Given the force and the charge of the particle experiencing the force, we can first compute the electric field at the observation location. Once the electric field is known, we can use the point-charge electric field model to solve for the unknown source charge. | ||

<table border> | <table border> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td> <b>Step 1.</b> Find the | <td> | ||

<math> F = | <b>Step 1.</b> Find the electric field using <math>\vec{F} = q\vec{E}</math>. | ||

<math> E = \frac{ | <math>\vec{E} = \frac{\vec{F}}{q}</math> | ||

<math> = \frac{\langle -5.5\times10^{3}, -5.5\times10^{3}, -5.5\times10^{3}\rangle}{-2\times10^{-3}}</math> | |||

= | <math> = \langle 2.75\times10^{6},\, 2.75\times10^{6},\, 2.75\times10^{6}\rangle</math> N/C | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td> | |||

<b>Step 2.</b> Compute <math>\vec{r}</math> from the particle at the origin to the observation location. | |||

<math>\vec{r} = \langle 3.98,\,3.98,\,3.98\rangle\ \text{m}</math> | |||

Magnitude: | |||

<math>|\vec{r}| = \sqrt{3.98^2 + 3.98^2 + 3.98^2}</math> | |||

<math>= \sqrt{47.52} \approx 6.89\ \text{m}</math> | |||

Unit vector: | |||

<math>\hat{r} = \frac{\vec{r}}{|\vec{r}|}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

< | <tr> | ||

<td> | |||

<b>Step 3.</b> Solve for the unknown charge using the point-charge field equation: | |||

<math>E_{mag}=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{|q|}{r^2}</math> | |||

Rearranged: | |||

<math>|q| = (4\pi\epsilon_0)\,(r^2)\,E_{mag}</math> | |||

<math> | Using <math>E_{mag} = 2.75\times10^{6}</math> N/C and <math>r = 6.89</math> m: | ||

<math> q= { | <math>|q| = (8.99\times10^{-12})(6.89^2)(2.75\times10^{6})</math> | ||

<math> q | <math>|q| \approx 0.237\ \text{C}</math> | ||

Sign of the charge: | |||

The force on the negative test charge is **toward** the origin → the source must be **positive**. | |||

<b>Final Answer:</b> | |||

<math>q_{\text{origin}} \approx +0.24\ \text{C}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table border> | </table border> | ||

====Common Mistakes==== | |||

* **Using the wrong sign for q.** | |||

Remember: if the force on a negative charge points toward the origin, the source must be positive. | |||

* **Forgetting that E and F point the same direction only for positive test charges.** | |||

Since the test charge is −2 mC, is opposite the force direction. | |||

* **Mixing up <math>\vec{r}</math> and <math>|\vec{r}|</math>.** | |||

One is a vector; the other is a scalar distance. | |||

* **Failing to use the magnitude of E when solving for |q|.** | |||

The field equation uses only magnitudes, not vector components. | |||

* **Using an incorrect value of Coulomb’s constant.** | |||

==Connectedness== | ==Connectedness== | ||

''1. How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in?'' | ''1. How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in?'' | ||

The topic is fascinating because electric fields not only exist within the human body but also in the realms of aerospace. It's captivating to think about the parallels between biological systems and aerospace systems, where electric field management is crucial for functions such as propulsion and navigation. Analyzing how bodies maintain and adapt their electric fields and applying this knowledge to aerospace engineering can lead to innovative approaches to energy management and system efficiency, particularly in the face of perturbations such as equipment failure or external environmental factors. | |||

''2. How is it connected to your major?'' | ''2. How is it connected to your major?'' | ||

As an aerospace engineer, my interest lies in the application of principles from various sciences, including biochemistry, to improve and innovate within the field of aviation and space exploration. Understanding the role of electric fields in cellular behavior provides insights into potential analogs in aerospace technology. For instance, similar to how cells adjust their electric fields for optimal function, aerospace systems must regulate their onboard electric fields for navigation, communication, and operational efficiency. Such interdisciplinary knowledge can be the foundation for advancements in aerospace materials and systems that are responsive and adaptive to their environments. | |||

''3. Is there an interesting industrial application?'' | ''3. Is there an interesting industrial application?'' | ||

PEMF | PEMF (Pulsed Electromagnetic Field) therapy's principle of restoring optimal voltage in damaged cells through electromagnetic fields has interesting parallels in aerospace engineering. For example, the management of electromagnetic fields is critical in spacecraft and aircraft to protect onboard electronics and enhance communication signals. The concept of PEMF can inspire the development of systems that can self-regulate and optimize electrical potential across different components of an aircraft or spacecraft, thereby enhancing performance and resilience. Such systems could prove vital in long-duration space missions, where human intervention is limited, and the machine's ability to self-heal and maintain operational integrity can be a game-changer. | ||

PEMF | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 246: | Line 295: | ||

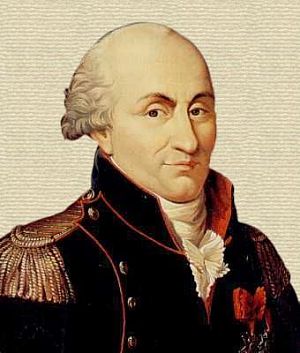

Charles de Coulomb was born in June 14, 1736 in central France. He spent much of his early life in the military and was placed in regions throughout the world. He only began to do scientific experiments out of curiously on his military expeditions. However, when controversy arrived with him and the French bureaucracy coupled with the French Revolution, Coulomb had to leave France and thus really began his scientific career. | Charles de Coulomb was born in June 14, 1736 in central France. He spent much of his early life in the military and was placed in regions throughout the world. He only began to do scientific experiments out of curiously on his military expeditions. However, when controversy arrived with him and the French bureaucracy coupled with the French Revolution, Coulomb had to leave France and thus really began his scientific career. | ||

Between 1785 and 1791, de Coulomb wrote several key papers centered around multiple relations of electricity and magnetism. This helped him develop the principle known as Coulomb's Law, which confirmed that the force between two electrical charges is directly proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. This is the same relationship that is seen in the electric field equation of a point charge. | Between 1785 and 1791, de Coulomb wrote several key papers centered around multiple relations of electricity and magnetism. This helped him develop the principle known as Coulomb's Law, which confirmed that the force between two electrical charges is directly proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. This is the same relationship that is seen in the electric field equation of a point charge. | ||

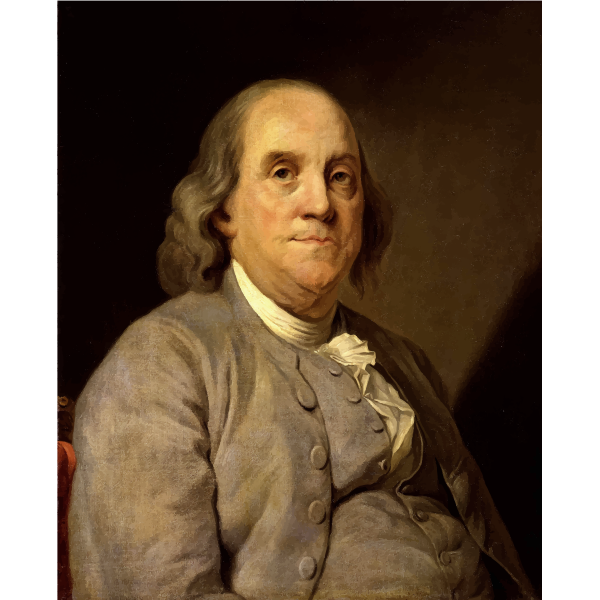

[[File:Benjamin-Franklin-Portrait.png]] | |||

''Benjamin Franklin'' | |||

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) made several foundational contributions to the early understanding of electric charge. Although he did not write mathematical laws like Coulomb, his ideas directly shaped the concepts used in point-charge physics. | |||

Franklin introduced the naming system of positive and negative charge, which is still used today. He proposed that charge behaves like a conserved quantity that can move between objects—an essential idea behind treating charges as isolated point charges located at specific positions in space. | |||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 267: | Line 323: | ||

Some more information: | Some more information: | ||

*http://www.physics.umd.edu/courses/Phys260/agashe/S10/notes/lecture18.pdf | *http://www.physics.umd.edu/courses/Phys260/agashe/S10/notes/lecture18.pdf | ||

*https://www.reliantphysicaltherapy.com/services/pulsed-electromagnetic-field-pemf | *https://www.reliantphysicaltherapy.com/services/pulsed-electromagnetic-field-pemf | ||

*https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HG9KxDZ-qwI&t=1s | |||

*https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GJf-Fj-qoI&t=3s | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 22:59, 23 November 2025

Claimed by Gabriel Cruz Fall 2025

This page is all about the Electric Field due to a Point Charge.

The Main Ideas

(Ch 13.1 in Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood)

Point Charge / Particle — an object whose radius is extremely small compared to the distances to other objects in the system. Because it is so small, all of its charge and mass can be treated as if they are concentrated at a single point.

- Electrons and protons are always treated as point particles unless stated otherwise.

Two types of point charges:

- **Protons ( +e )** → positive point charges, [math]\displaystyle{ q = +1.6\times10^{-19}\text{ C} }[/math]

- **Electrons ( –e )** → negative point charges, [math]\displaystyle{ q = -1.6\times10^{-19}\text{ C} }[/math]

Like point charges repel; opposite point charges attract.

| Point Charges | Result | Diagram |

|---|---|---|

| 1 proton, 1 electron | Attract |  |

| 2 protons | Repel |  |

| 2 electrons | Repel |  |

The Electric Field

(Ch 13.3 in Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood)

The electric field describes how a source charge influences the space around it. This field exists everywhere, even if no other charges are present to experience a force. The electric field allows interactions to occur at a distance.

It is important to note that **electric field is not the same as electric force**.

Electric Force due to an Electric Field:

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{F} = q\vec{E} }[/math]

- **F** = force on the particle

- **E** = electric field at the observation location

- **q** = charge of the particle (assume [math]\displaystyle{ 1.6\times10^{-19}\text{ C} }[/math] unless stated otherwise)

The electric field becomes weaker as the distance from the point charge increases.

| The electric field of a positive point charge points radially outward. | The electric field of a negative point charge points radially inward. |

|

|

A Mathematical Model

Electric Field Due to a Point Charge

(Ch 13.4 in Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood)

The magnitude of the electric field decreases with increasing distance from the point charge. This is described by:

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q}{|\vec{r}|^2}\hat{r} }[/math] (Newtons/Coulomb)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} }[/math] is Coulomb’s constant, approximately [math]\displaystyle{ 8.987\times10^{9}\frac{N\,m^2}{C^2} }[/math]

- **q** = charge of the source particle

- **r** = distance from source location to observation location

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} }[/math] = unit vector pointing from the source to the observation point

Reminder: [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} }[/math] always points from the source charge to the observation location.

The direction of the electric field depends on the sign of the source charge:

- If the source charge is positive → field points away (same direction as [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} }[/math])

- If the source charge is negative → field points toward the charge (opposite [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} }[/math])

Coulomb Force Law for Point Charges

(Ch 13.2 in Matter & Interactions Vol. 2: Modern Mechanics, 4th Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood)

[math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{F}| = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{|Q_1 Q_2|}{r^2} }[/math]

Coulomb’s Law describes the magnitude of the electric force between two point charges.

The full vector form is:

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{F} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{Q_1 Q_2}{r^2}\hat{r} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ Q_1, Q_2 }[/math] = the charges

- **r** = the distance between the two charges

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} }[/math] = Coulomb’s constant

Connection Between Electric Field and Force

The force on a test charge is given by [math]\displaystyle{ F = Eq }[/math].

Substituting Coulomb’s Law for **F**:

[math]\displaystyle{ E = \frac{F}{q_2} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q_1}{r^2}\hat{r} }[/math]

The similarity of the Coulomb force law and electric field equation comes from the fact that the electric field is the force per unit test charge:

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = \frac{\vec{F}}{q_{test}} }[/math]

Direction rules:

- If the source charge is positive → force and field point away from the charge

- If the source charge is negative → force and field point toward the charge

Electric Field Superposition (Point Charges)

When multiple point charges are present, the **net electric field** is the vector sum of the electric field from each charge:

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E}_{net} = \sum \vec{E}_i }[/math]

This is due to the principle of **superposition**: the total effect is the sum of individual effects.

Important reminders:

- A charge does not exert a force on itself

- Source charges are assumed not to move (so [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{F}_{net} = 0 }[/math])

A Computational Model

Below is a simulation showing the electric field at various observation locations around a proton. The arrows decrease in size according to [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{r^{2}} }[/math], showing how the electric field weakens with distance.

Two adjacent point charges of opposite sign form an electric dipole. The electric field points toward the negative charge (blue) and away from the positive charge (red).

A Computational Model 2

Click this link to see another computional model.

Examples

Simple

There is an electron at the origin. Calculate the electric field at <4, -3, 1> m.

Middling

A particle of unknown charge is located at <-0.21, 0.02, 0.11> m. Its electric field at point <-0.02, 0.31, 0.28> m is [math]\displaystyle{ \lt 0.124, 0.188, 0.109\gt }[/math] N/C. Find the magnitude and sign of the particle's charge.

Given both an observation location and a source location, one can find both r and [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} }[/math] Given the value of the electric field, one can also find the magnitude of the electric field. Then, using the equation for the magnitude of electric field of a point charge, [math]\displaystyle{ E_{mag}= \frac{1}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 } \frac{q}{r^2} }[/math] one can find the magnitude and sign of the charge.

| Step 1. Find [math]\displaystyle{ \vec r_{obs} - \vec r_{particle} }[/math]:

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec r = \lt -0.02, 0.31, 0.28\gt m - \lt -0.21, 0.02, 0.11\gt m = \lt 0.19,0.29,0.17\gt m }[/math] To find [math]\displaystyle{ \vec r_{mag} }[/math], find the magnitude of [math]\displaystyle{ \lt 0.19,0.29,0.17\gt }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{0.19^2+0.29^2+0.17^2}=\sqrt{0.1491}= 0.39 }[/math] |

| Step 2: Find the magnitude of the Electric Field:

[math]\displaystyle{ E= \lt 0.124, 0.188, 0.109\gt N/C }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ E_{mag} = (\sqrt{0.124^2+0.188^2+0.109^2}=\sqrt{0.0626}=0.25 }[/math] |

| Step 3: Find q by rearranging the equation for [math]\displaystyle{ E_{mag} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ E_{mag}= \frac{1}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 } \frac{q}{r^2} }[/math] By rearranging this equation we get [math]\displaystyle{ q= {4 \pi * \epsilon_0 } *{r^2}*E_{mag} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ q= {1/(9*10^9)} *{0.39^2}*0.25 }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ q= + 4.3*10^{-12} C }[/math] |

Difficult

The electric force on a -2 mC particle at location (3.98, 3.98, 3.98) m due to a particle at the origin is [math]\displaystyle{ \langle -5.5\times10^{3},\, -5.5\times10^{3},\, -5.5\times10^{3}\rangle }[/math] N. What is the charge on the particle at the origin?

Given the force and the charge of the particle experiencing the force, we can first compute the electric field at the observation location. Once the electric field is known, we can use the point-charge electric field model to solve for the unknown source charge.

|

Step 1. Find the electric field using [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{F} = q\vec{E} }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = \frac{\vec{F}}{q} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ = \frac{\langle -5.5\times10^{3}, -5.5\times10^{3}, -5.5\times10^{3}\rangle}{-2\times10^{-3}} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ = \langle 2.75\times10^{6},\, 2.75\times10^{6},\, 2.75\times10^{6}\rangle }[/math] N/C |

|

Step 2. Compute [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math] from the particle at the origin to the observation location. [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} = \langle 3.98,\,3.98,\,3.98\rangle\ \text{m} }[/math] Magnitude: [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{r}| = \sqrt{3.98^2 + 3.98^2 + 3.98^2} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ = \sqrt{47.52} \approx 6.89\ \text{m} }[/math] Unit vector: [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} = \frac{\vec{r}}{|\vec{r}|} }[/math] |

|

Step 3. Solve for the unknown charge using the point-charge field equation: [math]\displaystyle{ E_{mag}=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{|q|}{r^2} }[/math] Rearranged: [math]\displaystyle{ |q| = (4\pi\epsilon_0)\,(r^2)\,E_{mag} }[/math] Using [math]\displaystyle{ E_{mag} = 2.75\times10^{6} }[/math] N/C and [math]\displaystyle{ r = 6.89 }[/math] m: [math]\displaystyle{ |q| = (8.99\times10^{-12})(6.89^2)(2.75\times10^{6}) }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ |q| \approx 0.237\ \text{C} }[/math] Sign of the charge: The force on the negative test charge is **toward** the origin → the source must be **positive**. Final Answer: [math]\displaystyle{ q_{\text{origin}} \approx +0.24\ \text{C} }[/math] |

Common Mistakes

- **Using the wrong sign for q.**

Remember: if the force on a negative charge points toward the origin, the source must be positive.

- **Forgetting that E and F point the same direction only for positive test charges.**

Since the test charge is −2 mC, is opposite the force direction.

- **Mixing up [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{r}| }[/math].**

One is a vector; the other is a scalar distance.

- **Failing to use the magnitude of E when solving for |q|.**

The field equation uses only magnitudes, not vector components.

- **Using an incorrect value of Coulomb’s constant.**

Connectedness

1. How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in?

The topic is fascinating because electric fields not only exist within the human body but also in the realms of aerospace. It's captivating to think about the parallels between biological systems and aerospace systems, where electric field management is crucial for functions such as propulsion and navigation. Analyzing how bodies maintain and adapt their electric fields and applying this knowledge to aerospace engineering can lead to innovative approaches to energy management and system efficiency, particularly in the face of perturbations such as equipment failure or external environmental factors.

2. How is it connected to your major?

As an aerospace engineer, my interest lies in the application of principles from various sciences, including biochemistry, to improve and innovate within the field of aviation and space exploration. Understanding the role of electric fields in cellular behavior provides insights into potential analogs in aerospace technology. For instance, similar to how cells adjust their electric fields for optimal function, aerospace systems must regulate their onboard electric fields for navigation, communication, and operational efficiency. Such interdisciplinary knowledge can be the foundation for advancements in aerospace materials and systems that are responsive and adaptive to their environments.

3. Is there an interesting industrial application?

PEMF (Pulsed Electromagnetic Field) therapy's principle of restoring optimal voltage in damaged cells through electromagnetic fields has interesting parallels in aerospace engineering. For example, the management of electromagnetic fields is critical in spacecraft and aircraft to protect onboard electronics and enhance communication signals. The concept of PEMF can inspire the development of systems that can self-regulate and optimize electrical potential across different components of an aircraft or spacecraft, thereby enhancing performance and resilience. Such systems could prove vital in long-duration space missions, where human intervention is limited, and the machine's ability to self-heal and maintain operational integrity can be a game-changer.

History

Charles de Coulomb was born in June 14, 1736 in central France. He spent much of his early life in the military and was placed in regions throughout the world. He only began to do scientific experiments out of curiously on his military expeditions. However, when controversy arrived with him and the French bureaucracy coupled with the French Revolution, Coulomb had to leave France and thus really began his scientific career.

Between 1785 and 1791, de Coulomb wrote several key papers centered around multiple relations of electricity and magnetism. This helped him develop the principle known as Coulomb's Law, which confirmed that the force between two electrical charges is directly proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. This is the same relationship that is seen in the electric field equation of a point charge.

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) made several foundational contributions to the early understanding of electric charge. Although he did not write mathematical laws like Coulomb, his ideas directly shaped the concepts used in point-charge physics.

Franklin introduced the naming system of positive and negative charge, which is still used today. He proposed that charge behaves like a conserved quantity that can move between objects—an essential idea behind treating charges as isolated point charges located at specific positions in space.

See also

Electric Field

Electric Force

Superposition Principle

Electric Dipole

Further reading

Principles of Electrodynamics by Melvin Schwartz ISBN: 9780486134673

Electricity and Magnetism: Edition 3 , Edward M. Purcell David J. Morin

External links

Some more information:

- http://www.physics.umd.edu/courses/Phys260/agashe/S10/notes/lecture18.pdf

- https://www.reliantphysicaltherapy.com/services/pulsed-electromagnetic-field-pemf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HG9KxDZ-qwI&t=1s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GJf-Fj-qoI&t=3s

References

Chabay. (2000-2018). Matter & Interactions (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

PY106 Notes. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2016, from http://physics.bu.edu/~duffy/py106.html

Retrieved November 28, 2016, from http://www.biography.com/people/charles-de-coulomb-9259075#controversy-and-absolution