Conductors

Created by David Nam Spring 2025, Claimed/Edited by Jacob Buzzard Fall 2025

The Main Idea

A conductor is a material in which charged particles can freely move. In most conductors, such as metals, the outer (valence) electrons are loosely bound, forming what is described as a sea of electrons. These "free" electrons easily move under the influence of an external electric field or potential difference, allowing electric current to easily flow.

In electrostatic equilibrium, charges within a conductor rearrange themselves so that the net electric field inside the conductor is zero. Any excess charge resides entirely on the conductor's surface, and the potential is constant throughout the interior. If a conductor is placed within an external electric field, the mobile electrons inside move almost instantaneously to reach equilibrium, setting up an induced field within the material that cancels the external one. This follows an "equal and opposite" rule, so that the induced and external electric fields cancel each other out. This induced charge movement, opposite to the net external electric field, explains important physics phenomena, such as:

- Electric shielding (Faraday cages)

- Because the electric field inside a conductor is zero, a closed conducting shell, called a Faraday cage, can protect its interior from the influence of external electric fields.

- Induced charge seaparation on conductor surfaces

- When a neutral conductor is placed in an external electric field, its free electrons shift opposite the field's direction. This creates a region of excess negative charge on one side and excess positive charge on the other. Though the conductor remains overall neutral (as charge is conserved), this polarization allows it to interact with nearby charges.

- Uniform potential inside conducting objects

- Since charges move freely within the conductor until equilibrium is reached, every point inside a conductor shares the same electric potential, in other words, the potential is uniform. At equilibrium, this means no current flows within the conductor, and the potential difference between any two points inside the conductor is zero.

Conductors are essential to the flow of electric current in circuits. When connected to a voltage source, like a battery, the applied potential difference drives electrons through the conductor, producing a measurable current. The ability of a material to conduct depends on its atomic structure, external temperature, and geometry. Metals such as Cu, Ag, and Al are excellent conductors due to their high density of free electrons.

Because conductors inherently allow charge to move readily, they are used to transmit electrical energy in an efficient manner, used in real-life scenarios such as circuits and power lines. Their behavior under external electric fields forms a foundation for understanding resistance, capacitance, circuits, and electromagnetic induction.

Factors Affecting Conductance

There are some factors that can change the conductance of a conductor. Shape and size, for example, affect the conductance of an object. A thicker(larger cross sectional area A as shown in the diagram) piece will be a better conductor than a thinner piece of the same material and other dimensions. This is the same concept that a thicker piece of wire allows for greater current flow. The larger cross sectional area allows for more flow of charge carriers. A shorter conductor will also conduct better since it has less resistance than a longer piece. Conductance itself can also change conductivity. In actively conducting electric current, the conductor heats up. This is secretly the third factor affecting conductance: temperature. Changes in temperature can cause the same object to have a different conductance under otherwise identical conditions. The most well known example of this is glass. Glass is more of an insulator at typical to cold temperatures, but becomes a good conductor at higher temperatures. Generally, metals are better conductors at cooler temperatures. This is because an increase in temperature is an increase in energy, specifically for electrons.

A Microscopic Model

Microscopically, conductors are made up of a lattice of positively charged nuclei surrounded by freely moving electrons throughout the material. These electrons are known as delocalized electrons, meaning that they are not bound to any specific atom, instead moving randomly within the solid.

When no external electric field is applied, the motion of these electrons is random, resulting in no net current. However, when an electric field is introduced, these electrons experience a force opposite the direction of the field and begin to drift slightly with a drift velocity. Although this drift velocity is small, the large amount of electrons collectively moving produces an observable electric current.

There is a relationship between conductivity and temperature: as temperature increases, the amount of phonons, or what we can see as the vibration of atoms in the lattice, increases. This increased number of phonons scatters these freely moving electrons more frequently, increasing resistance, and therefore decreasing conductivity.

From a quantum-mechanical and materials science perspective, the behavior of conductors is governed by their energy band structure. In solids, closely spaced atomic orbitals overlap to form continuous ranges of energy that are known as bands. In conductors (metals), the valence band, which contains the outer (valence) electrons and the conduction band either overlap or have a nonexistent band gap. Because of this overlap, electrons can esaily move to higher-energy states and flow under even a weak electric field.

A Mathematical Model

Ohm's Law of J = σE can be used to model the relationship of conductivity to electric current density where J is electric current density, σ is conductivity of the material, and E is electric field. This is a generalized form of the well known V = IR.

σ is larger for better conductors like metals and saltwater. For "perfect" conductors, σ approaches infinity. In this case, E would be zero since the current density J cannot be infinity.

Materials are generally divided into three categories based on σ:

- Lossless Materials: σ = 0

- Lossy Materials: σ > 0

- Conductors: σ >> 0

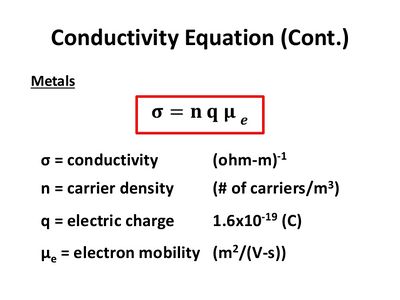

Below is a breakdown of how conductivity is calculated. This could be considered a formula for conductivity, but it would be more accurate to think of it as a definition.

Conductivity can also be explained as the inverse of resistivity. σ = 1/ρ where ρ is resistivity.

A Computational Model

This simple interactive is a great way to see which real objects are made of conducting or insulating material. Try to guess which objects will allow for flow of electricity before you test with the interactive.

https://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/semiconductor

Examples

Simple

Material A has a resitivity of [math]\displaystyle{ 5.90 \cdot 10^{-8} Ω \cdot m }[/math] and Material B has a conductivity of [math]\displaystyle{ 1.00 \cdot 10^7 S/m }[/math]. They are the same size and temperature. Which is a better conductor?

We can change Material A's resitivity to conductivity with the formula σ = 1/ρ. σ = [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{(5.90 \cdot 10^{-8} Ω \cdot m)} = 1.69 \cdot 10^7 S/m }[/math]. Since Material A has a greater conductivity, it is a better conductor.

These numbers are the real conductivities of Zinc(Material A) and Iron(Material B).

Middling

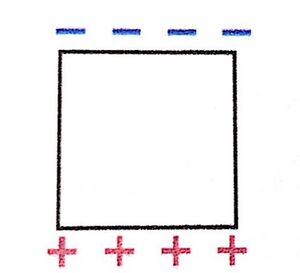

A negatively charged iron block is placed in a region where there is an electric field downward (in the -y direction). What will be the charge distribution of the iron block in this field? (Problem 47 from Matter and Interactions, page 583)

Remember that in the direction of an electric field is traditionally the direction of positive charge movement. Since the iron block is a conductor, it has electrons that are free to move and will travel opposite the direction of the electric field. This will leave an excess of positive charge at the bottom of the block and an excess of negative charge at the top of the block, as shown in the diagram.

Difficult

This should be completed by a student

solution

Connectedness

- How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in?

- How is it connected to your major?

- Is there an interesting industrial application?

History

Modern research on electricity and conductors starts in the 1700s. Many different scientists contributed to the research that led to the understanding and use of conductors. Stephan Gray was one of the first of these, first studying the idea of electricity and then conductors. In Gray's time, the general consensus was that "electric virtue" was a quality that some materials could attain and others could not. Some materials, like glass, could acquire electric virtue by friction, while others, like metal, could be given electric virtue by contact with a charged object. Gray tested this theory with many different types of material, even with a child(who did work as a conductor).

Dufay began research on the same topics of charge transfer and conductance just after Gray. He lengthened the list of objects that could be given electric virtue by friction. Dufay also named the growing categories. "Electrical bodies" were what we call insulators and "non-electric bodies" were what we know as conductors. While this seems backwards from the way we think about insulators and conductors, it comes from the idea that electric virtue was intrinsic to insulators because charge could be induced on these simply by friction, while conductors can only come to have a charge by contact with a charged insulator.

Only when Benjamin Franklin came around some later did the ideology and vocabulary make a big switch. Franklin suggested that electricity is not created by electrical bodies through friction, but that it is a fluid shared by all bodies and can pass between them. Franklin also caused the shift in language from non-electric bodies to conductors and electric bodies to non-conductors.

There is some evidence that ancient Egyptians also used electricity.

See also

Further reading

To learn more about conductors:

External links

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BY8ZPobU8B0

- https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-physics-1/ap-electric-charge-electric-force-and-voltage/conservation-of-charge-ap/v/conductors-and-insulators

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PafSqL1riS4

References

- Benjamin, Park. A History of Electricity (The Intellectual Rise of Electricity) from Antiquity to the Days of Benjamin Franklin. J. Wiley & Sons, 1898. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=K2dDAAAAIAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=ancient egypt electricity&ots=edMffcocC0&sig=zFX9kUz2FKoPcPTCf8YVId2AjhQ#v=onepage&q&f=false.