Escape Velocity: Difference between revisions

Tdellaert3 (talk | contribs) |

Anguyen676 (talk | contribs) (references. broken url) |

||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File: | [[File:Voyager Path czech version.jpg|400px|thumb|right|A diagram showing the paths of Voyager 1 and 2.]] | ||

Edited by Alexander Nguyen, Fall 2025 | |||

Escape velocity is the minimum initial speed required for an object to overcome the gravitational attraction of a massive body and reach an infinitely large distance without further propulsion. It is derived from conservation of mechanical energy. An object launched at escape speed will continue slowing due to gravity, but it will never reverse direction and fall back. Gravitational force and acceleration remain nonzero at all finite distances; only as <math>r \rightarrow \infty</math> do they approach zero. | |||

==The Main Idea== | ==The Main Idea== | ||

The formula for escape velocity at a | The formula for escape velocity at a given distance from a body is calculated by the formula | ||

:<math>v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}},</math> | :<math>v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}},</math> | ||

where <math>G</math> is the universal [[gravitational constant]] (<math>G = 6. | where <math>G</math> is the universal [[gravitational constant]] (<math>G = 6.67430\times 10^{-11}\,\text{m}^3\text{kg}^{-1}\text{s}^{-2}</math>), <math>M</math> is the mass of the large body to be escaped, and <math>r</math> the distance from the [[center of mass]] of the mass <math>M</math> to the object. This equation assumes there are no other forces acting on either body. As a side note, the escape velocity stated here could really be called escape speed due to the fact that the quantity is independent of direction. Notice that the equation does not include the mass of the orbiting body. | ||

===A Mathematical Model=== | ===A Mathematical Model=== | ||

The escape velocity condition is obtained from conservation of mechanical energy. Consider the system consisting of a planet of mass <math>M</math> and an object of mass <math>m</math> launched from radius <math>r</math>. | |||

Initial energy: | |||

<math> | |||

E_i = K_i + U_i = \frac{1}{2}mv_e^2 - \frac{GMm}{r} | |||

</math> | |||

:<math> | Final state at infinity: | ||

<math> | |||

K_f = 0,\quad U_f = 0 | |||

</math> | |||

Thus, | |||

<math> | |||

E_i = E_f = 0 | |||

</math> | |||

Solving, | |||

<math> | |||

\frac{1}{2}mv_e^2 - \frac{GMm}{r} = 0 | |||

</math> | |||

<math> v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} </math> | |||

Because <math>m</math> cancels, escape velocity is independent of the mass of the escaping object. Only the central body mass and launch radius matter. | |||

'''Bound versus unbound systems''' | |||

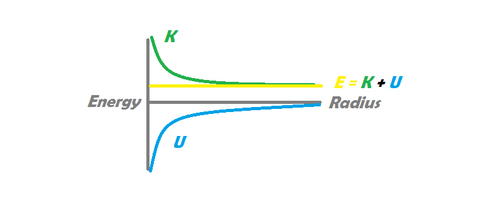

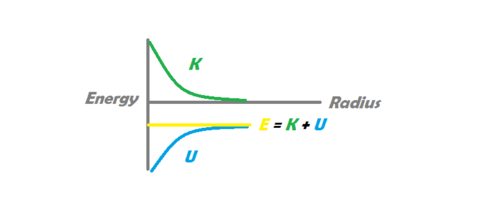

When an object is orbiting a massive body, it can be in one of two states: bound and unbound. If the object is in a bound state, we see an elliptical trajectory, in which the orbiting body never escapes the gravitational influence of the more massive body. In an unbound state, however, we observe a parabolic or hyperbolic trajectory, in which the object is able to escape the gravitational influence of the orbiting body and In a bound system, the total mechanical energy satisfies <math>E < 0</math>. In a marginally unbound trajectory (parabolic), <math>E = 0</math>. In a hyperbolic trajectory, <math>E > 0</math>. The diagram to the left shows an unbound system, in which the sum of the kinetic and potential energy of the orbiting body is greater than 0. As distance goes to infinity in this system, gravitational potential energy approaches zero, but the object retains a positive kinetic energy, and therefore a positive velocity. The image on the right shows a bound system, in which the sum of the kinetic and potential energy is negative. In this system, kinetic energy reaches zero at a specific maximum distance, at which point the object begins to fall back towards the massive body, never to escape. | |||

When an object is orbiting a massive body, it can be in one of two states: bound and unbound. If the object is in a bound state, we see an elliptical trajectory, in which the orbiting body never escapes the gravitational influence of the more massive body. In an unbound state, however, we observe a parabolic or hyperbolic trajectory, in which the object is able to escape the gravitational influence of the orbiting body and | |||

[[File:Ediagram_MSPaint_UnboundSystemWithExtraEnergy.png|500px|thumb|left|The energy diagram of an unbound system, in which the object has excess kinetic energy. The vertical axis represents energy, while the horizontal axis represents distance. At exactly the escape velocity, the sum of <math>K</math> and <math>U</math> is exactly 0.]] | [[File:Ediagram_MSPaint_UnboundSystemWithExtraEnergy.png|500px|thumb|left|The energy diagram of an unbound system, in which the object has excess kinetic energy. The vertical axis represents energy, while the horizontal axis represents distance. At exactly the escape velocity, the sum of <math>K</math> and <math>U</math> is exactly 0.]] | ||

| Line 37: | Line 48: | ||

<br clear=all> | <br clear=all> | ||

== | ===A Computational Model=== | ||

The PhET Gravity and Orbits simulation allows experimentation with orbital trajectories. To explore escape velocity: | |||

* Select the single planet–satellite system. | |||

* Place the satellite at a fixed launch radius. | |||

* Increase the initial launch speed gradually. | |||

* When the trajectory transitions from elliptical to open, the launch speed is equal to or greater than the escape velocity at that radius. | |||

Compare this observed value to <math>v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}}</math>. | |||

===Middling=== | |||

'''Question 1''' | |||

If the escape velocity of a planet with the same mass as Earth is greater than the escape velocity of Earth, is the planet larger or smaller than Earth? | |||

'''Solution 1''' | |||

Given the formula: <math> v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} </math> | |||

And rearranging for radius: <math> r = \frac{2GM}{v^2_e} </math> | |||

We can see that since the denominator of the faction is larger with a constant numerator, then the radius must be smaller. Therefore, the planet is smaller than Earth. | |||

'''Question 2''' | |||

v = 4.76 m/s | |||

'''Solution 2''' | |||

The escape velocity is the minimum velocity required to escape the gravitational field of a planet, so the object must have kinetic energy greater than or equal to its potential energy. | |||

34 = \frac{1}{2} m v^2 | |||

v^2 = (2*34)/3 | |||

v = 4.76 m/s | |||

===Difficult=== | |||

'''Question 1''' | |||

The radius of Jupiter is <math>71.5\times 10^6 \text{m}</math>, and its mass is <math>1900\times 10^{24} \text{kg}</math>. What is the escape speed of an object launched straight up from just above the atmosphere of Jupiter? | The radius of Jupiter is <math>71.5\times 10^6 \text{m}</math>, and its mass is <math>1900\times 10^{24} \text{kg}</math>. What is the escape speed of an object launched straight up from just above the atmosphere of Jupiter? | ||

'''Solution 1''' | |||

<div style=""> | <div style=""> | ||

| Line 49: | Line 100: | ||

v_i = ?\\ | v_i = ?\\ | ||

v_f = 0 \text{m/s}\\ | v_f = 0 \text{m/s}\\ | ||

r_i = | r_i = 71.5\times 10^6 \text{m}\\ | ||

r_f = \infty\\ | r_f = \infty\\ | ||

m = m_{Object}\\ | m = m_{Object}\\ | ||

| Line 69: | Line 120: | ||

\frac{GM}{r_i} = \frac{1}{2}v_i^2\\ | \frac{GM}{r_i} = \frac{1}{2}v_i^2\\ | ||

v_i = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r_i}}\\ | v_i = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r_i}}\\ | ||

= \sqrt{\frac{2(6. | = \sqrt{\frac{2(6.67430\times 10^{-11} \text{N}\cdot\text{m}^2 / \text{kg}^2)(1900\times 10^{24} \text{kg})}{(71.5\times 10^6 \text{m})}}\\ | ||

= 5.97 \times 10^4 \text{m/s} | = 5.97 \times 10^4 \text{m/s} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

'''Question 2''' | |||

Jupiter has 318 times the mass of the Earth, and its radius is 11.2 times that of the Earth. Calculate the escape velocity of a body from Jupiter’s surface assuming that the escape velocity from Earth’s surface is 11.2 Km/s. | |||

'''Solution 2''' | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

v_e = \sqrt{\frac{ | |||

= | v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM_e}{r_e}}= 11.2 km/s | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</ | <math> | ||

v_j = \sqrt{\frac{2GM_j}{r_j}} | |||

</math> | |||

<math> | |||

M_j = 318M_e \text{ and } R_j = 11.2R_e | |||

</math> | |||

Therefore, | |||

<math> | |||

v_j = \sqrt{\frac{2G(318M_r)}{11.2R_e}} = 59.7 km/s | |||

</math> | |||

===Interactive Gravity Assist Simulation=== | |||

This model uses GlowScript VPython to simulate a Voyager-style gravity assist. The spacecraft approaches a moving planet, accelerates through its gravitational field, and departs with a different heliocentric velocity. | |||

[https://trinket.io/glowscript/47e96432cb8f Interactive Gravity Assist Model (Click to Run)] | |||

'''How to use:''' | |||

* Press **Run** in the Trinket window. | |||

* Observe the spacecraft trajectory as it approaches the planet. | |||

* Vary the spacecraft’s initial velocity vector in the code. | |||

* If the final trajectory is open (hyperbolic), the spacecraft has gained enough energy to become unbound. | |||

* If the final trajectory is closed (elliptic), it remains gravitationally bound. | |||

[[File:Gravityassist_screenshot.png|500px|thumb|center|A spacecraft gaining energy from a planetary flyby.]] | |||

==Connectedness== | ==Connectedness== | ||

In real life, escape velocity is not as easy to calculate as in the above examples. The primary complicating factor is the fact that there are more than two bodies in the universe, so in systems with multiple massive attracting bodies, escape velocity can become more complicated. One example is the escape velocity of an object from Earth: an object that achieves the escape velocity of Earth could theoretically escape Earth's influence, but it would remain in orbit around the sun unless its speed were much greater. The concept of escape velocity is widely used in orbital mechanics and rocketry and is critical for the planning of space missions. | |||

==Common Misconceptions== | |||

Escape velocity does not mean the object stops feeling gravity. | |||

Gravity acts at every finite distance; the object simply never reverses direction. | |||

Rockets do not necessarily need to reach escape velocity. | |||

Continuous thrust can exceed gravitational potential without ever reaching the escape speed. | |||

Escape velocity is not about height, it is about total energy. | |||

Even at high altitude, if total mechanical energy is negative, the trajectory is still bound. | |||

Orbital velocity is not “half” of escape velocity. | |||

They differ because they represent different energy configurations: | |||

<math>v_\text{orbit} = \sqrt{GM/r}</math>, | |||

<math>v_\text{escape} = \sqrt{2GM/r}</math>. | |||

==Escape Velocity vs. Orbital Velocity== | |||

Escape velocity is often confused with orbital velocity, but the two describe fundamentally different physical conditions. Orbital velocity corresponds to the circular speed that produces a stable bound orbit. Escape velocity corresponds to the minimum speed at which an object becomes unbound. Both follow from conservation of mechanical energy. | |||

The circular orbital speed at radius <math>r</math> around a body of mass <math>M</math> is obtained by balancing gravitational and centripetal acceleration: | |||

<math> \frac{GMm}{r^2} = \frac{mv^2}{r} </math> | |||

Solving, | |||

<math> | |||

v_\text{orbit} = \sqrt{\frac{GM}{r}} | |||

</math> | |||

Escape velocity, derived from the boundary condition <math>E = 0</math>, is: | |||

<math> v_\text{escape} = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} </math> | |||

Thus, | |||

<math> | |||

v_\text{escape} = \sqrt{2},v_\text{orbit} | |||

</math> | |||

This relationship is universal for Newtonian gravitational fields and independent of the escaping object’s mass. A satellite moving at orbital speed remains bound and repeatedly returns to the same radius. A spacecraft exceeding escape velocity has enough total energy to reach infinite separation, entering a parabolic (<math>E = 0</math>) or hyperbolic (<math>E > 0</math>) trajectory depending on its excess kinetic energy. | |||

==Escape Velocity and Black Holes== | |||

At sufficiently high mass density, the escape velocity can exceed the speed of light. Using Newtonian gravity, the escape speed from a spherical body of mass <math>M</math> and radius <math>r</math> is | |||

:<math>v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}}.</math> | |||

If we set <math>v_e = c</math>, where <math>c</math> is the speed of light, we obtain the radius at which light would just be able to escape: | |||

:<math>c = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}},</math> | |||

which leads to | |||

:<math>r = \frac{2GM}{c^2}.</math> | |||

This radius is called the Schwarzschild radius, denoted <math>r_s</math>: | |||

:<math>r_s = \frac{2GM}{c^2}.</math> | |||

Any mass compressed inside this radius forms a black hole. Although the above derivation is Newtonian, the same expression for <math>r_s</math> appears as the exact solution to the Einstein field equations for a non-rotating, uncharged black hole. | |||

==History== | |||

The concept of escape velocity originates from early studies of gravity. In the 17th century, Isaac Newton showed that the same gravitational force responsible for falling objects also governs planetary motion. He proposed the “Newton’s Cannonball” thought experiment, suggesting that if a projectile were launched with sufficient horizontal speed, it would never hit the Earth and instead orbit indefinitely. A higher speed would allow it to leave Earth entirely, anticipating the modern idea of escape velocity. | |||

The first real applications appeared centuries later during the development of spaceflight in the mid-20th century. Early chemical rockets lacked the thrust-to-weight ratios to reach escape speed, but improvements in guidance and staged propulsion made it feasible. In 1959, the Soviet spacecraft Luna 1 became the first human-made object to exceed Earth’s escape velocity, entering a heliocentric orbit instead of impacting the Moon. | |||

==See Also== | |||

===Further Reading=== | |||

https://www.nasa.gov/audience/foreducators/k-4/features/F_Escape_Velocity.html | |||

http://www.qrg.northwestern.edu/projects/vss/docs/space-environment/2-whats-escape-velocity.html | |||

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/escape-velocity. | |||

===External links=== | ===External links=== | ||

| Line 94: | Line 251: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

“A Brief History of Space Exploration.” The Aerospace Corporation, The Aerospace Corporation, 1 June 2018, aerospace.org/article/brief-history-space-exploration. | |||

"Escape Velocity | Physics." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2015. | "Escape Velocity | Physics." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2015. | ||

[http://www.britannica.com/science/escape-velocity] | [http://www.britannica.com/science/escape-velocity] | ||

NASA. "Escape Velocity." NASA Space Math, 2018. | |||

https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/Numbers/escapevelocity.html | |||

“Escape Velocity Formula - with Solved Examples.” Physicscatalyst's Blog, 4 Nov. 2022, https://physicscatalyst.com/article/escape-velocity-formula/#.Y41KpuzMKrc. | |||

Giancoli, Douglas C. | |||

Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics, 4th Edition. | |||

Pearson, 2009. | |||

“Gravity And Orbits.” PhET, University of Colorado Boulder, 5 Aug. 2019, phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/gravity-and-orbits. | |||

“Luna 1.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Nov. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luna_1. | |||

Velocity, Escape, and ©200. ESCAPE VELOCITY EXAMPLES (n.d.): n. pag. 13 June 2003. Web. 5 Dec. 2015. | Velocity, Escape, and ©200. ESCAPE VELOCITY EXAMPLES (n.d.): n. pag. 13 June 2003. Web. 5 Dec. 2015. | ||

[http://www.beaconlearningcenter.com/documents/1483_01.pdf] | [http://www.beaconlearningcenter.com/documents/1483_01.pdf] | ||

[[Category:Energy]] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:15, 2 December 2025

Edited by Alexander Nguyen, Fall 2025

Escape velocity is the minimum initial speed required for an object to overcome the gravitational attraction of a massive body and reach an infinitely large distance without further propulsion. It is derived from conservation of mechanical energy. An object launched at escape speed will continue slowing due to gravity, but it will never reverse direction and fall back. Gravitational force and acceleration remain nonzero at all finite distances; only as [math]\displaystyle{ r \rightarrow \infty }[/math] do they approach zero.

The Main Idea

The formula for escape velocity at a given distance from a body is calculated by the formula

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}}, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] is the universal gravitational constant ([math]\displaystyle{ G = 6.67430\times 10^{-11}\,\text{m}^3\text{kg}^{-1}\text{s}^{-2} }[/math]), [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is the mass of the large body to be escaped, and [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] the distance from the center of mass of the mass [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] to the object. This equation assumes there are no other forces acting on either body. As a side note, the escape velocity stated here could really be called escape speed due to the fact that the quantity is independent of direction. Notice that the equation does not include the mass of the orbiting body.

A Mathematical Model

The escape velocity condition is obtained from conservation of mechanical energy. Consider the system consisting of a planet of mass [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] and an object of mass [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] launched from radius [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math].

Initial energy: [math]\displaystyle{ E_i = K_i + U_i = \frac{1}{2}mv_e^2 - \frac{GMm}{r} }[/math]

Final state at infinity: [math]\displaystyle{ K_f = 0,\quad U_f = 0 }[/math]

Thus, [math]\displaystyle{ E_i = E_f = 0 }[/math]

Solving, [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{2}mv_e^2 - \frac{GMm}{r} = 0 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} }[/math]

Because [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] cancels, escape velocity is independent of the mass of the escaping object. Only the central body mass and launch radius matter.

Bound versus unbound systems

When an object is orbiting a massive body, it can be in one of two states: bound and unbound. If the object is in a bound state, we see an elliptical trajectory, in which the orbiting body never escapes the gravitational influence of the more massive body. In an unbound state, however, we observe a parabolic or hyperbolic trajectory, in which the object is able to escape the gravitational influence of the orbiting body and In a bound system, the total mechanical energy satisfies [math]\displaystyle{ E \lt 0 }[/math]. In a marginally unbound trajectory (parabolic), [math]\displaystyle{ E = 0 }[/math]. In a hyperbolic trajectory, [math]\displaystyle{ E \gt 0 }[/math]. The diagram to the left shows an unbound system, in which the sum of the kinetic and potential energy of the orbiting body is greater than 0. As distance goes to infinity in this system, gravitational potential energy approaches zero, but the object retains a positive kinetic energy, and therefore a positive velocity. The image on the right shows a bound system, in which the sum of the kinetic and potential energy is negative. In this system, kinetic energy reaches zero at a specific maximum distance, at which point the object begins to fall back towards the massive body, never to escape.

A Computational Model

The PhET Gravity and Orbits simulation allows experimentation with orbital trajectories. To explore escape velocity:

- Select the single planet–satellite system.

- Place the satellite at a fixed launch radius.

- Increase the initial launch speed gradually.

- When the trajectory transitions from elliptical to open, the launch speed is equal to or greater than the escape velocity at that radius.

Compare this observed value to [math]\displaystyle{ v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} }[/math].

Middling

Question 1

If the escape velocity of a planet with the same mass as Earth is greater than the escape velocity of Earth, is the planet larger or smaller than Earth?

Solution 1

Given the formula: [math]\displaystyle{ v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} }[/math]

And rearranging for radius: [math]\displaystyle{ r = \frac{2GM}{v^2_e} }[/math]

We can see that since the denominator of the faction is larger with a constant numerator, then the radius must be smaller. Therefore, the planet is smaller than Earth.

Question 2

v = 4.76 m/s

Solution 2

The escape velocity is the minimum velocity required to escape the gravitational field of a planet, so the object must have kinetic energy greater than or equal to its potential energy.

34 = \frac{1}{2} m v^2 v^2 = (2*34)/3 v = 4.76 m/s

Difficult

Question 1

The radius of Jupiter is [math]\displaystyle{ 71.5\times 10^6 \text{m} }[/math], and its mass is [math]\displaystyle{ 1900\times 10^{24} \text{kg} }[/math]. What is the escape speed of an object launched straight up from just above the atmosphere of Jupiter?

Solution 1

System = Jupiter + object [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta E = 0\\ v_i = ?\\ v_f = 0 \text{m/s}\\ r_i = 71.5\times 10^6 \text{m}\\ r_f = \infty\\ m = m_{Object}\\ M = m_{Jupiter} = 1900\times 10^{24} \text{kg} \\ }[/math]

Starting from the Energy Principle:

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta E = W + Q\\ \Delta E = 0 + 0 = 0\\ \Delta K + \Delta U = 0\\ \frac{1}{2}m(v_f^2-v_i^2) + (\frac{-GMm}{r_f} - \frac{-GMm}{r_i}) = 0\\ \frac{1}{2}m(0-v_i^2) + (0 - \frac{-GMm}{r_i}) = 0\\ -\frac{1}{2}mv_i^2 + \frac{GMm}{r_i} = 0\\ \frac{GMm}{r_i} = \frac{1}{2}mv_i^2\\ \frac{GM}{r_i} = \frac{1}{2}v_i^2\\ v_i = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r_i}}\\ = \sqrt{\frac{2(6.67430\times 10^{-11} \text{N}\cdot\text{m}^2 / \text{kg}^2)(1900\times 10^{24} \text{kg})}{(71.5\times 10^6 \text{m})}}\\ = 5.97 \times 10^4 \text{m/s} }[/math]

Question 2

Jupiter has 318 times the mass of the Earth, and its radius is 11.2 times that of the Earth. Calculate the escape velocity of a body from Jupiter’s surface assuming that the escape velocity from Earth’s surface is 11.2 Km/s.

Solution 2

[math]\displaystyle{ v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM_e}{r_e}}= 11.2 km/s }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ v_j = \sqrt{\frac{2GM_j}{r_j}} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ M_j = 318M_e \text{ and } R_j = 11.2R_e }[/math]

Therefore,

[math]\displaystyle{ v_j = \sqrt{\frac{2G(318M_r)}{11.2R_e}} = 59.7 km/s }[/math]

Interactive Gravity Assist Simulation

This model uses GlowScript VPython to simulate a Voyager-style gravity assist. The spacecraft approaches a moving planet, accelerates through its gravitational field, and departs with a different heliocentric velocity.

Interactive Gravity Assist Model (Click to Run)

How to use:

- Press **Run** in the Trinket window.

- Observe the spacecraft trajectory as it approaches the planet.

- Vary the spacecraft’s initial velocity vector in the code.

- If the final trajectory is open (hyperbolic), the spacecraft has gained enough energy to become unbound.

- If the final trajectory is closed (elliptic), it remains gravitationally bound.

Connectedness

In real life, escape velocity is not as easy to calculate as in the above examples. The primary complicating factor is the fact that there are more than two bodies in the universe, so in systems with multiple massive attracting bodies, escape velocity can become more complicated. One example is the escape velocity of an object from Earth: an object that achieves the escape velocity of Earth could theoretically escape Earth's influence, but it would remain in orbit around the sun unless its speed were much greater. The concept of escape velocity is widely used in orbital mechanics and rocketry and is critical for the planning of space missions.

Common Misconceptions

Escape velocity does not mean the object stops feeling gravity. Gravity acts at every finite distance; the object simply never reverses direction.

Rockets do not necessarily need to reach escape velocity. Continuous thrust can exceed gravitational potential without ever reaching the escape speed.

Escape velocity is not about height, it is about total energy. Even at high altitude, if total mechanical energy is negative, the trajectory is still bound.

Orbital velocity is not “half” of escape velocity. They differ because they represent different energy configurations: [math]\displaystyle{ v_\text{orbit} = \sqrt{GM/r} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ v_\text{escape} = \sqrt{2GM/r} }[/math].

Escape Velocity vs. Orbital Velocity

Escape velocity is often confused with orbital velocity, but the two describe fundamentally different physical conditions. Orbital velocity corresponds to the circular speed that produces a stable bound orbit. Escape velocity corresponds to the minimum speed at which an object becomes unbound. Both follow from conservation of mechanical energy.

The circular orbital speed at radius [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] around a body of mass [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is obtained by balancing gravitational and centripetal acceleration:

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{GMm}{r^2} = \frac{mv^2}{r} }[/math]

Solving, [math]\displaystyle{ v_\text{orbit} = \sqrt{\frac{GM}{r}} }[/math]

Escape velocity, derived from the boundary condition [math]\displaystyle{ E = 0 }[/math], is:

[math]\displaystyle{ v_\text{escape} = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} }[/math]

Thus, [math]\displaystyle{ v_\text{escape} = \sqrt{2},v_\text{orbit} }[/math]

This relationship is universal for Newtonian gravitational fields and independent of the escaping object’s mass. A satellite moving at orbital speed remains bound and repeatedly returns to the same radius. A spacecraft exceeding escape velocity has enough total energy to reach infinite separation, entering a parabolic ([math]\displaystyle{ E = 0 }[/math]) or hyperbolic ([math]\displaystyle{ E \gt 0 }[/math]) trajectory depending on its excess kinetic energy.

Escape Velocity and Black Holes

At sufficiently high mass density, the escape velocity can exceed the speed of light. Using Newtonian gravity, the escape speed from a spherical body of mass [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] and radius [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] is

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}}. }[/math]

If we set [math]\displaystyle{ v_e = c }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] is the speed of light, we obtain the radius at which light would just be able to escape:

- [math]\displaystyle{ c = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}}, }[/math]

which leads to

- [math]\displaystyle{ r = \frac{2GM}{c^2}. }[/math]

This radius is called the Schwarzschild radius, denoted [math]\displaystyle{ r_s }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ r_s = \frac{2GM}{c^2}. }[/math]

Any mass compressed inside this radius forms a black hole. Although the above derivation is Newtonian, the same expression for [math]\displaystyle{ r_s }[/math] appears as the exact solution to the Einstein field equations for a non-rotating, uncharged black hole.

History

The concept of escape velocity originates from early studies of gravity. In the 17th century, Isaac Newton showed that the same gravitational force responsible for falling objects also governs planetary motion. He proposed the “Newton’s Cannonball” thought experiment, suggesting that if a projectile were launched with sufficient horizontal speed, it would never hit the Earth and instead orbit indefinitely. A higher speed would allow it to leave Earth entirely, anticipating the modern idea of escape velocity.

The first real applications appeared centuries later during the development of spaceflight in the mid-20th century. Early chemical rockets lacked the thrust-to-weight ratios to reach escape speed, but improvements in guidance and staged propulsion made it feasible. In 1959, the Soviet spacecraft Luna 1 became the first human-made object to exceed Earth’s escape velocity, entering a heliocentric orbit instead of impacting the Moon.

See Also

Further Reading

https://www.nasa.gov/audience/foreducators/k-4/features/F_Escape_Velocity.html

http://www.qrg.northwestern.edu/projects/vss/docs/space-environment/2-whats-escape-velocity.html

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/escape-velocity.

External links

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/bring-science-home-reaction-time/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7w56rwAtUZU

References

“A Brief History of Space Exploration.” The Aerospace Corporation, The Aerospace Corporation, 1 June 2018, aerospace.org/article/brief-history-space-exploration.

"Escape Velocity | Physics." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2015. [1]

NASA. "Escape Velocity." NASA Space Math, 2018. https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/Numbers/escapevelocity.html

“Escape Velocity Formula - with Solved Examples.” Physicscatalyst's Blog, 4 Nov. 2022, https://physicscatalyst.com/article/escape-velocity-formula/#.Y41KpuzMKrc.

Giancoli, Douglas C. Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics, 4th Edition. Pearson, 2009.

“Gravity And Orbits.” PhET, University of Colorado Boulder, 5 Aug. 2019, phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/gravity-and-orbits.

“Luna 1.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Nov. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luna_1.

Velocity, Escape, and ©200. ESCAPE VELOCITY EXAMPLES (n.d.): n. pag. 13 June 2003. Web. 5 Dec. 2015. [2]