Electric Potential

The Main Idea

Electric Potential Energy, like all forms of potential energy, is the potential for work to be done, in this case by the electric force. The Electric Potential (frequently referred to as voltage, from its SI unit, the Volt) is the Electric Potential Energy associated with the test charge (1 Coulomb), such that it depends only on the source, just as the electric field is related to the electric force, but depends only on the source. One may similarly remember the parallel concept of the gravitational potential, which was gravitational potential energy divided by mass.

A Mathematical Model

Electric Potential Energy is defined with respect to the Electric Force & Electric Field:

- [math]\displaystyle{ U_{ab} = - q \int_{b}^{a} \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{L} }[/math], where

- [math]\displaystyle{ U_{ab} }[/math] is the Electric Potential Energy from point b to point a

- [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] is the charge in the electric field

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E} }[/math] is the source charge's electric field

- [math]\displaystyle{ d\mathbf{L} }[/math] is a differential length along the path from point b to point a

- [math]\displaystyle{ U_{ab} = - q \int_{b}^{a} \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{L} }[/math], where

The differential work [math]\displaystyle{ (dW) }[/math] associated with an external force [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathbf{F}_{ext}) }[/math] moving a charge [math]\displaystyle{ (q) }[/math] from point b to point a [math]\displaystyle{ (d\mathbf{L}) }[/math] through an electric field [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathbf{E}) }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ dW = \mathbf{F}_{ext} \cdot d\mathbf{L} }[/math]

- This is the vector multiplication of the force moving the charge and the distance the object has moved.

The external force must be equal and opposite to the force associated with the source charge's electric field:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{F}_{ext} &= - \mathbf{F}_{E} \\ &= - q \mathbf{E} \end{align} }[/math]

Therefore:

- [math]\displaystyle{ dW = - q \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{L} }[/math]

Integrating from point b to point a along the path gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = -q \int_{b}^{a} \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{L} }[/math]

Finally, since the work was defined externally, the calculated work is equal to the Electric Potential Energy:

- [math]\displaystyle{ U_{ab} = -q \int_{b}^{a} \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{L} }[/math]

From this, the Electric Potential is defined as the Electric Potential Energy per test charge in the source charge's electric field:

- [math]\displaystyle{ V_{ab} = \frac{U_{ab}}{q} = - \int_{b}^{a} \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{L} }[/math]

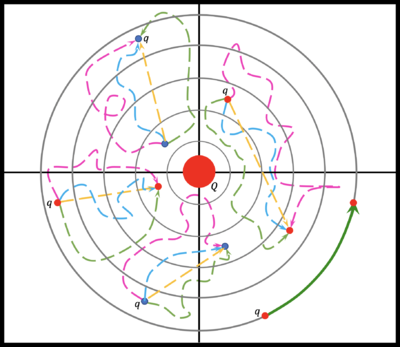

- The electric field is a conservative vector field:

- This means that any path used in the above line integral will give the same value for the same beginning and end points (b and a). Looking at the figure to the right, many paths for a charge [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] subject to the electric field of source charge [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math] are shown. In each set of four paths (Green, Blue, Yellow, and Pink), the same amount of Electric Potential Energy and Electric Potential is gained or lost.

- A special case shown in dark green near the bottom right of the figure also exists:

- If a charge is moving along a path that is always perpendicular to the electric field, the line integral will evaluate to zero, and therefore the Electric Potential Energy and Electric Potential will also evaluate to zero.

- This is easily shown with the dot product; if two variable vectors are always perpendicular, then their dot product is always zero.

- The Electric Potential between two point charges [math]\displaystyle{ (Q \ \text{and} \ q) }[/math] can be written in a simpler expression:

- [math]\displaystyle{ V_{ab} = \frac{q}{4 \pi \epsilon_{0}} \biggr ( \frac{1}{r_{a}} - \frac{1}{r_{b}} \biggr ) }[/math], where

- [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] is the charge in the source's electric field

- [math]\displaystyle{ r_{a} }[/math] is the final position

- [math]\displaystyle{ r_{b} }[/math] is the initial position

- [math]\displaystyle{ V_{ab} = \frac{q}{4 \pi \epsilon_{0}} \biggr ( \frac{1}{r_{a}} - \frac{1}{r_{b}} \biggr ) }[/math], where

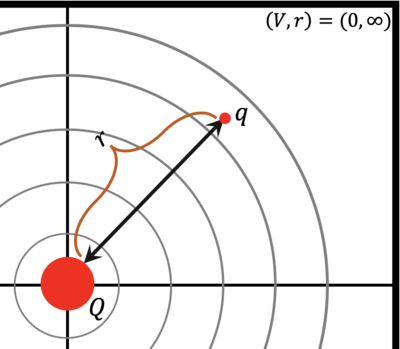

- The initial position is often taken to be infinity (the Electric Potential is defined to be zero at infinity) creating a simpler and more familiar looking equation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ V_{ab} = \frac{q}{4 \pi \epsilon_{0} r} }[/math], where

- [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] is the distance between the source charge and the charge in the electric field

- [math]\displaystyle{ V_{ab} = \frac{q}{4 \pi \epsilon_{0} r} }[/math], where

- This is used to described the Electric Potential gained or lost when moving a charge radially closer to a source charge.

A Computational Model

Examples

Simple

Middling

Difficult

Connectedness

History

See also

Further reading

Externals links

References

The Main Idea

Electric potential energy, like all forms of potential energy, is the potential for work to be done, in this case by the electric force. The electric potential (frequently referred to as voltage, from its SI unit the Volt) is the electric potential energy associated with the test charge, such that it depends only on the source, just as the electric field is related to the electric force, but depends only on the source. One may similarly remember the parallel concept of the gravitational potential, which was gravitational potential energy divided by mass.

Mathematical Model

Electric Potential Energy

Electric potential energy may be calculated in a variety of manners, depending upon the situation. The electric potential energy between two point charges may be written in a form which follows directly from the definition of the Coulomb force:

[math]\displaystyle{ U = \frac{qQ}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r_0} }[/math]

This is the amount of energy which would be required to bring one of the charged objects (by convention the small [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] charge) from an infinite distance to its current position, where, by convention, the potential energy at infinity is equal to zero. This may, therefore, be derived from the equation for work:

Derivation with Calculus

[math]\displaystyle{ U = -W = -\int_\infty^{r_0} \vec{F}_E(r) \cdot \text{d} \vec{r} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ U = -\int_\infty^{r_0} \frac{qQ \hat{r}}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r^2} \cdot \text{d} \vec{r} = -\frac{qQ}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\int_\infty^{r_0} \frac{\hat{r} \cdot \hat{r}}{r^2} \text{d} r }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ U = \frac{qQ}{4\pi \epsilon_0} \biggr{(} \frac{1}{r} \biggr{|}_{\infty}^{r_0} = \frac{qQ}{4\pi \epsilon_0 r_0} }[/math]

Given our definition of the Electric Field, we have that

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{F}_E(r) = q\vec{E} }[/math]

so the electric potential energy may be generally written as

[math]\displaystyle{ U = -q\int_a^b \vec{E} \cdot \text{d} \vec{r} }[/math]

Linear assumption

From the above equation, one can see that if the electric field is constant over the length of the path, then electric potential energy may be written in a simplified manner as

[math]\displaystyle{ U = q\vec{E}\cdot\Delta \vec{s} }[/math]

Electric Potential

Just as we divided by charge to go from electric force to electric field, dividing by charge takes us from the electric potential energy to the electric potential. For a test particle of charge [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math], we define

[math]\displaystyle{ V = \frac{U}{q} }[/math]

Derivation with Calculus

This is not especially meaningful without choosing a reference point, just as for potential energy. Thus, one may speak of the potential difference between two points, which is independent of the reference value. From the above definition of electric potential energy, it is possible to derive an expression for the potential difference between two points from the electric field:

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta V = -\int_a^b \vec{E} \cdot \text{d} \vec{s} }[/math]

The vectors are used to express the path associated with this integral. The difference in electric potential will be the same no matter what path one takes, as explored in Path Independence of Electric Potential. This also allows one to write the inverse relationship, determining the electric field at a given point from the electric potential in one and three dimensions respectively:

[math]\displaystyle{ E = -\frac{\text{d}V}{\text{d}x} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = -\nabla V }[/math]

Where [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math] is the gradient operator.

Linear Assumption

The above equations allow us to write the equivalent expressions under an assumption of constant values for the electric field, such that the integral reduces to

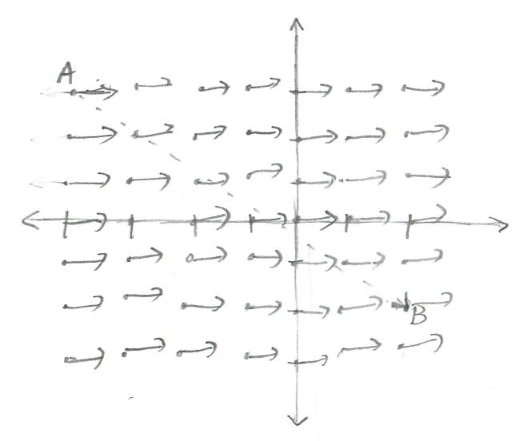

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta V = -\vec{E} \cdot \Delta \vec{l} = -(E_x \Delta x + E_y \Delta y + E_z \Delta z) }[/math]

This also leads directly to the inverse expression:

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = -(\frac{\Delta V_x}{\Delta x} + \frac{\Delta V_y}{\Delta y} + \frac{\Delta V_z}{\Delta z}) }[/math]

The electric potential difference in a field which is nonuniform, but whose variations are discrete, is [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta V = -\sum \vec{E}\cdot \Delta\vec{l} }[/math]. The different parts in this particular equation resembles the equation for the potential difference in an uniform field, except that with the nonuniform field, the potential difference in the different fields are summed up. This situation can be quite easy, but when the system gets difficult, first, choose a path and divide it into smaller pieces of [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta\vec{l} }[/math]; second, write an expression for [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{V} = -\vec{E}\cdot\Delta\vec{l} }[/math] of one piece; third, add up the contributions of all the pieces; last, check the result to make sure the magnitude, direction, and units make sense.

It is important to keep track of the sign differences. If the path follows the direction of the electric field, the sign of the potential difference will be negative. This may be imagined as dropping a positive test charge in an electric field: a positive charge will be accelerated in the direction of the field, meaning that it is gaining energy, and so its potential must be decreasing. By contrast, if the path is opposite the direction of the field, potential will be increasing, much like rolling a boulder up a hill. If the path is perpendicular to the direction of the electric field, the dot product will be equal to zero.

Also, when working with different situations, it is nice to keep in mind that in a conductor, the electric field is zero. Therefore, the potential difference is zero as well. In an insulator, the electric field is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{E_{applied}}{K} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is the dielectric constant. Furthermore, the potential difference over a round trip is equal to zero.

A Computational Model

Click on the link to see Electric Potential through VPython!

Make sure to press "Run" to see the principle in action!

Watch this video for a more visual approach!

Electric Potential: Visualizing Voltage with 3D animations

Examples

Simple

In a capacitor, the negative charges are located on the left plate, and the positive charges are located on the right plate. Location A is at the left end of the capacitor, and Location B is at the right end of the capacitor, or in other words, Location A and B are only different in terms of their x component location. The path moves from A to B. What is the direction of the electric field? Is the potential difference positive or negative?

Answer: The electric field is to the left. The potential difference is increasing, or is positive.

Explanation: The electric field always moves away from the positive charge and towards the negative charge, which means the electric field in this example is to the left. Because the direction and the electric field and the direction of the path are opposite, the potential difference is increasing, or is positive.

Middling

Calculate the change in electric potential between point A, which is at [math]\displaystyle{ (-4, 3,0) \; m }[/math], and B, which is at [math]\displaystyle{ (2,-2,0) \; m }[/math] . The electric field in the location is [math]\displaystyle{ (50,0,0) \; N/C }[/math].

Answer: -300V

Explanation:

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta\vec{l}= (2,-2,0)\;m - (-4,3,0)\;m = (6,-5,0)\;m }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{V} = -({E}_{x}∆{x} + {E}_{y}∆{y} + {E}_{z}∆{z}) }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{V} = -(50\; N/C \cdot 6 \;m + 0 \; N/c \cdot -5 \; m + 0\cdot 0) }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{V} = -300 V }[/math]

Difficult

The Bohr Model of the hydrogen atom treats it as a nucleus of charge [math]\displaystyle{ +e }[/math] electrons of charge [math]\displaystyle{ -e }[/math] orbiting in circular orbits of specific radii. Calculate the potential difference between two points, one infinitely far away from the nucleus, and the other one Bohr radius [math]\displaystyle{ a_0 }[/math] away from the nucleus (don't worry about substituting in the values). Compute the electric potential energy associated with the electron one Bohr radius away from the nucleus, setting the potential energy at infinity as zero (remember the sign of the charge).

We may compute the electric potential by taking integrating the electric field of a point charge as the radius goes from infinity to [math]\displaystyle{ a_0 }[/math]. This integral may be set up as:

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta V = -\int_\infty^{a_0} \vec{E}\cdot\text{d}\vec{l} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta V = -\frac{e}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int_\infty^{a_0} \frac{\text{d} r}{r^2} }[/math]

This may then be solved:

[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta V = \frac{e}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\biggr{(}\frac{1}{r}\biggr{|}_\infty^{a_0} = \frac{e}{4\pi\epsilon_0 a_0} }[/math]

to compute the potential energy, we now multiply by the charge of the electron: [math]\displaystyle{ -e }[/math], giving

[math]\displaystyle{ U = -\frac{e^2}{4\pi\epsilon_0 a_0} }[/math]

Depending on what physics or chemistry courses you may have taken before, this may be recognizable as twice the ionization energy of the n=1 orbital. The factor of two is due to the fact that in the Bohr model, the kinetic energy will be exactly half of this potential energy, and will be positive so that the net result is still negative, but with half the magnitude. This understanding of the hydrogen atom gets certain values right, but the reality of the situation is far more complicated.

Connectedness

How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in?

[Author] I am interested in robotic systems and building circuit boards and electrical systems for manufacturing robots. While studying this section in the book, I was able to connect back many of the concepts and calculations back to robotics and the electrical component of automated systems.

[Revisionist] Since high school, I never really understood how to work with the voltmeter and what it measured, and I have always wanted to know, but although this particular wiki page did not go into the details and other branches of electric potential, it led me to find the answers to something I was interested in since high school, the concept of electric potential.

[Editor] I think electively is really interesting. When I was younger, I participated in this demo where a group of people hold hands and someone touches this special ball full of charge. We all could feel the tingling sensation of the current passing through us. It’s cool to learn the theory behind the supposed magic that occurs.

[FALL 2018] I think it's very interesting that electric potential can be seen as a property of a space and that we can have further applications using this property.

How is it connected to your major?

[Author] I am a Mechanical Engineering major, so I will be dealing with the electrical components of machines when I work. Therefore, I have to know these certain concepts such as electric potential in order to fully understand how they work and interact.

[Revistionist] As a biochemistry major, electric potential and electric potential difference is not particularly related to my major, but in chemistry classes, we use electrostatic potential maps (electrostatic potential energy maps) that shows the charge distributions throughout a molecule. Although the main use in electric potential is different in physics and biochemistry (where physicists use it identify the effect of the electric field at a location), I still found it interesting as the concept of electric potential (buildup) was being used in quite a different way.

[Editor] I am a computer science major. Although I deal mostly with software, the hardware aspect is still important. The algorithms that I design run differently on different machines. The time complexity of an algorithm is sometimes useless when worrying about constant factors that are determined by a system’s hardware. Quicksort, for instance, is usually faster than many other sorts that have lower time complexities. The hardware of computers heavily relies on electricity and current (which is induced by a potential difference) to switch transistors on and off and thereby process information.

[FALL 2018] I am an aerospace engineering major, and I think understanding such concepts will help me have a better holistic understanding towards fields and systems. In addition, the thinking behind solving related problems will help me better prepared for future classes that involve with solving dynamics problems.

Is there an interesting industrial application?

[Author] Electrical potential is used to find the voltage across a path. This is useful when working with circuit components and attempting to manipulate the power output or current throughout a component.

[Revisionist] Electric potential sensors are being used to detect a variety of electrical signals made by the human body, thus contributing to the field of electrophysiology.

[Editor] The study of electric potential has lead scientists to generate very safe wires that will not overheat and cause fires. Connecting circuits to ground is important and the third prong in an electrical outlet is this ground connection.

History

The idea of electric potential, in a way, started with Ben Franklin and his experiments in the 1740s. He began to understand the flow of electricity, which eventually paved the path towards explaining electric potential and potential difference. Scientists finally began to understand how electric fields were actually affecting the charges and the surrounding environment. Benjamin Franklin first shocked himself in 1746, while conducting experiments on electricity with found objects from around his house. Six years later, or 261 years ago for us, the founding father flew a kite attached to a key and a silk ribbon in a thunderstorm and effectively trapped lightning in a jar. The experiment is now seen as a watershed moment in mankind's venture to channel a force of nature that was viewed quite abstractly.

By the time Franklin started experimenting with electricity, he'd already found fame and fortune as the author of Poor Richard's Almanack. Electricity wasn't a very well understood phenomenon at that point, so Franklin's research proved to be fairly foundational. The early experiments, experts believe, were inspired by other scientists' work and the shortcomings therein.

source: http://www.benjamin-franklin-history.org/kite-experiment/

That early brush with the dangers of electricity left an impression on Franklin. He described the sensation as "a universal blow throughout my whole body from head to foot, which seemed within as well as without; after which the first thing I took notice of was a violent quick shaking of my body." However, it didn't scare him away. In the handful of years before his famous kite experiment, Franklin contributed everything from designing the first battery designs to establishing some common nomenclature in the study of electricity. Although Franklin is often coined the father of electricity, after he set the foundations of electricity, many other scientists contributed his or her research in the advancement of electricity and eventually led to the discovery of electric potential and potential difference.

See also

Like mentioned multiple times throughout the page, although electric potential is a huge and important topic, it has many branches, which makes the concept of electric potential difficult to stand alone. Even with this page, to support the concept of electric potential, many crucial branches of the topic appeared, like potential difference (which also branched into [Potential Difference Path Independence], [Potential Difference In A Uniform Field], and [Potential Difference In A Nonuniform Field]).

External Links

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pcWz4tP_zUw

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vpa_uApmNoo

References

[1] "Benjamin Franklin and Electricity." Benjamin Franklin and Electricity. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Apr. 2016. <http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/franklinb/aa_franklinb_electric_1.html>.

[2] Bottyan, Thomas. "Electrostatic Potential Maps." Chemwiki. N.p., 02 Oct. 2013. Web. 17 Apr. 2016. <http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Core/Theoretical_Chemistry/Chemical_Bonding/General_Principles_of_Chemical_Bonding/Electrostatic_Potential_maps>.

[3] "Electric Potential Difference." Electric Potential Difference. The Physics Classroom, n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2016. <http://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/circuits/Lesson-1/Electric-Potential-Difference>.

[4] Harland, C. J., T. D. Clark, and R. J. Prance. "Applications of Electric Potential (Displacement Current) Sensors in Human Body Electrophysiology." International Society for Industrial Process Tomography, n.d. Web. 16 Apr. 2016. <http://www.isipt.org/world-congress/3/269.html>.

[5] Sherwood, Bruce A. "2.1 The Momentum Principle." Matter & Interactions. By Ruth W. Chabay. 4th ed. Vol. 1. N.p.: John Wiley & Sons, 2015. 45-50. Print. Modern Mechanics.