Specific Heat

CLAIMED BY MEGAN STEVENS 4-17-16

Specific heat, also known as the specific heat capacity, is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of a unit mass by one degree Celsius. The units for specific heat are Joules per gram-degree Celsius (J / g °C). Specific heat is important as it can determine the thermal interaction a material has with other materials. We can test the validity of models with specific heat since it is experimentally measurable. The study of thermodynamics was sparked by the research done on specific heat. Thermodynamics is the study of the conversion of energy involving heat and temperature change of a system.

The Main Idea

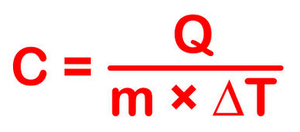

The most common definition is that specific heat is the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of a mass by 1 degree Celsius. The specific heat of a substance depends on its phase (solid, liquid, or gas) and its molecular structure. The relationship between heat and temperature change is best defined by constant "c" in the equation below.

To calcuate specfic heat, use the formula;

where the mass is in grams and temperature is in degrees Celsius.

This equation does not apply if a phase change occurs (say from a liquid state to a gaseous state). This is because the amount of heat added or removed during a phase change does not change the overall temperature of the substance. So we disregard this relationship when phase changes take place.

The specific heat for solid can be calculated by the change in energy of the atoms over the change in temperature. The change in energy of the atom is calculated by dividing the change in the energy of the system by the number of atoms in the substance.

The specific heat most commonly known is the specific heat for water, which is 4.186 joule/gram °C or 1 calorie/gram °C. Water has a very large specific heat on a per-gram basis which means that it is very difficult to cause a change in its temperature. Since the specific heat of water is so high, water can be used for temperature regulation. Due to the difference in their atomic structures, the specific heat per gram for water is much higher than that for a metal. It is possible to predict the specific heat of an material, if you know about its atomic structure, as a rise in temperature is the increase in energy at the atomic level of substances. Generally, it is more more useful to compare specific heats on a molecular level.

There are two ways to determine the specific heats of substances at the atomic level. These are the Dulong-Petit Law and the Einstein-Deybe model. The molar specific heats of most solids at room temperature are practically constant, which agrees with the Law of Dulong and Petit. At lower temperatures, the specific heats drop as atomic processes become more relevant. This behavior is explained by the Einstein-Debye model of specific heat.

Law of Dulong and Petit

[edit]

In 1819, French physicists, Pierre Louis Dulong and Alexis Thérèse Petit, discovered that the average molar specific heat for metals are approximately the same and equal to 25 J mole-1 oC-1 or roughly 3R where R is the gas constant for one mole. In this law, the amount of heat required to change the temperature is dependent on the number of molecules in the substance and not the mass.

Example The specific heat of copper is 0.386 Joules/gram degrees Celsius while the specific heat of Aluminum is 0.900 Joules/gram Celsius. Why is there such a difference? Specific heat is measured in Energy per unit mass, but it should be measured in Energy per mole for more similar specific heats for solids. The similar molar specific heats for solid metals are what define the Law of Dulong and Petit.

The specific heats of metals, therefore should all be around 24.94 J/mol degrees Celsius. The specific heat at constant volume should be just the temperature derivative of that energy.

Copper 0.386 J/gm K x 63.6 gm/mol = 24.6 J/mol K

Aluminum 0.900 J/gm K x 26.98 gm/ mol = 24.3 J/mol K

Einstein Debye Model

[edit]

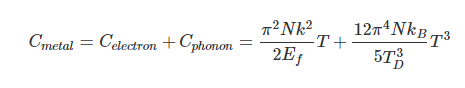

Einstein and Debye had developed models for specific heat separately with Einstien's model saying that low energy excitation of a solid material was caused by oscillation of a single atom, whereas Debye's model stated that phonons or collective modes iterating through the material caused the excitations. However, these two models are able to be extended together to find the specific heat given by the formula:

For low temperatures, Einstein and Debye found that the Law of Dulong and Petit was not applicable. At lower temperatures, it was found that atomic interactions were deemed significant in calculating the molar specific heat of an object.

According to the Einstein Debye Model for Copper and Aluminum, two solid metals, specific heat varies much at lower temperatures and goes much below the Dulong-Petit Model. This is due to increased effects on specific heat by interatomic forces. However, for very high temperature values, the Einstein-Debye Model cannot be used. In fact, at high temperatures, Einstein's expression of specific heat, reduces to the Dulong-Petit mathematical expression.

Here is the Einstein Debye Equation:

For high Temperatures it may be reduced like this:

This actually reduces to the Dulong-Petit Formula for Specific Heat:

Specific Heats of Gases

Specific heats of gases are generally expressed in their molar form due to the undefined volume or pressure of a gas. Usually only volume or pressure is held constant at a time. The first law of Thermodynamics helps to derive the formulas for specific heat for constant pressure and the specific heat for constant volume. Here is the equation:

There are two specific heats for gases, one for gases at a constant volume and one gases at a constant pressure. In the formula below, the gas has a constant volume:

where Q is heat, n is number of moles, and delta T is change in Temperature.

For an ideal monatomic gas, the molar specific heat should be around:

For a constant pressure, specific heat can be derived as:

where Q is heat, n is number of moles, and delta T is change in Temperature.

For and ideal monatomic gas, the molar specific heat should be around:

The molar specific heats of gases all gravitate towards these ranges depending on the conditions the gas is kept in.

Connectedness

Specific heat and thermodynamics are used often in chemistry, nuclear engineering, aerodynamics, and mechanical engineering. It is also used in everyday life in the radiator and cooling system of a car.

- Specific heat can have a lot to do with prosthetic manufacturing, which is huge in Biomedical Engineering. Prosthetics materials must be durable and easy to manipulate in a normal range of temperatures. In order to created medical devices, specific heats must be known, especially for welding or molding things, which require a specific temperature to be effective. At higher temperatures, the Dulong-Petit law must be used to calculate the specific heat of an object. Especially for solid metal objects, which would be used in prosthetics, Dulong-Petit is especially useful.

See also

Heat Capacity

External links

References

This section contains the the references you used while writing this page:

http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/emcon.html#emcon

http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/thermo/spht.html

http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/physics/SpecificHeat.html

http://www.tutorvista.com/content/physics/physics-iii/heat-and-thermodynamics/dulong-and-petit-law.php

Matter & Interactions Vol I. Chabay Sherwood

Claimed by Felix Joseph

Main page

Recent changes

Random page

Help

Tools

What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Printable version Permanent link Page information

This page was last modified on 29 November 2015, at 23:04. This page has been accessed 525 times. Privacy policy About Physics Book Disclaimers