Gravitational Force Near Earth: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

DylanJMount (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''[ | '''[[Dylan Mount – Spring 2025]''' This section describes gravitational force near Earth's surface, including applications and relevant derivations. | ||

==Main Idea== | ==Main Idea== | ||

Close to the surface of the Earth, the acceleration caused by gravity remains roughly the same. Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation tells us that every pair of masses pulls on each other. The strength of this attraction depends on how big the masses are and how far apart they are from each other. | |||

When we think of Earth as a point mass, we can say that an object sitting on the surface is about one Earth radius away from the center of our planet. The height of most everyday objects is so tiny compared to the vast radius of the Earth that the difference in distance is practically unnoticeable. This explains why we can consider gravitational acceleration g to be constant near the surface of the Earth. | |||

===A Mathematical Model=== | ===A Mathematical Model=== | ||

| Line 16: | Line 17: | ||

Since the only forces acting on a object in free fall near earth's surface are it's weight, (mass and gravity), we can set <math> {F}_{grav} = {mg} </math> ,and then plug that into Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation. After canceling out the constants, we arrive at the gravitational constant for a free falling object near earth. | Since the only forces acting on a object in free fall near earth's surface are it's weight, (mass and gravity), we can set <math> {F}_{grav} = {mg} </math> ,and then plug that into Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation. After canceling out the constants, we arrive at the gravitational constant for a free falling object near earth. | ||

::<math> {g} = \frac{GM_{Earth}}{R_{Earth}^2}</math> | |||

Near Earth's surface ''g'' is unchanging. As such, we define it as the gravitational constant near Earth's surface, ''g'', which is approximately <math>9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} </math>. This calculation is shown below: | |||

::<math>C= \frac{(6.67*10^{-11} \frac{m^3}{kgs})(5.972*10^{24} kg)}{(6.378*10^{6} m)^2} = 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2}</math> | ::<math>C= \frac{(6.67*10^{-11} \frac{m^3}{kgs})(5.972*10^{24} kg)}{(6.378*10^{6} m)^2} = 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2}</math> | ||

This then puts the force near Earth due to gravity into a much simpler form: | This then puts the force near Earth due to gravity into a much simpler form: | ||

| Line 29: | Line 30: | ||

::* ''m'' is the mass of the object whose behavior we are interested in | ::* ''m'' is the mass of the object whose behavior we are interested in | ||

The gravitation constant ''g'' applies to all masses significantly smaller than Earth's mass. These masses will all fall at the same acceleration. | The gravitation constant ''g'' applies to all masses ''significantly'' smaller than Earth's mass. These masses will all fall at the same acceleration. | ||

===The Gravitational Field=== | ===The Gravitational Field=== | ||

[[File:Newtons2LawImage344.png|thumb|left|Distance between the centers of mass of Earth and an object on its surface to be the radius of Earth.]] | |||

The gravitational field shows us how a mass affects the space that surrounds it. The strength of the field at a specific point influences the gravitational force that a mass feels when it is positioned there. | |||

Field lines move toward the center of the Earth and become more concentrated as the strength of the field increases. | |||

[[File:Gravitational field Earth lines equipotentials.svg|thumb|Gravitational field lines]] | |||

The gravitational field strength can be expressed in vector form as: | |||

:: <math> \vec g = \frac{GM}{r^2} \hat r\ </math> | :: <math> \vec g = \frac{GM}{r^2} \hat r\ </math> | ||

'''Conceptual Question''': Say you are standing in the basement of a building and weigh yourself. Then you immediately go to the 10th floor of the same building and weigh yourself again. Is your weight the same? | |||

::Your weight is ''not'' the same, however the significance that it changes is negligible if you are just traveling to the top of a building. Although you are further from the Earth's center of mass, the difference in distance from the Earth's center of mass is too small to significantly change your weight. Although your weight may change in varying levels due to your distance from Earth's surface, your mass will always stay the same. This is because <math> {F} = {ma} </math> | |||

===Common Misunderstandings About Gravity=== | |||

Some common beliefs about gravity might not be as accurate as we think. Addressing these misunderstandings fosters a deeper understanding of physics and helps prevent typical errors during exams. | |||

'''1. "Heavier objects tend to fall faster than those that are lighter."''' | |||

This isn't true when air resistance is not a factor. Close to the surface of our planet, everything falls at the same speed, with an acceleration of <math> g = 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} </math>, no matter how heavy or light it is. Although heavier objects feel a stronger gravitational ''force'' (as described by <math> F = mg </math>), they do ''not'' undergo a greater acceleration. | |||

'''2. "Astronauts in orbit feel weightless."''' | |||

Astronauts remain firmly within the embrace of Earth's gravitational pull. They float because they are constantly falling towards Earth, which gives us that feeling of weightlessness. At typical orbital altitudes, gravity remains roughly 90% of what we experience on the surface. | |||

'''3. " No matter where you are on Earth, your weight remains constant."''' | |||

The weight of an object is influenced by how far it is from the center of the Earth and the way mass is distributed within the Earth itself. Your weight is a bit lighter at the equator due to the Earth's larger radius in that region, while you feel a bit heavier at the poles. The variations may be slight, yet they can be quantified. | |||

===A Computational Model=== | ===A Computational Model=== | ||

Using the approximation derived above, we can create a computational model for the force of gravity near Earth's surface by applying Newton's second law in an iterative fashion to update acceleration, velocity, and finally position. This allows us to simulate the motion of an object near Earth's surface using only its mass. Seen below is a GlowScript code snippet accomplishing this iterative update technique. | Using the approximation derived above, we can create a computational model for the force of gravity near Earth's surface by applying Newton's second law in an iterative fashion to update acceleration, velocity, and finally position. This allows us to simulate the motion of an object near Earth's surface using only its mass. Seen below is a GlowScript code snippet accomplishing this iterative update technique. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 68: | ||

::ball.pos = ball.pos + ball.vel * deltat | ::ball.pos = ball.pos + ball.vel * deltat | ||

</code> | </code> | ||

===When the Constant-g Assumption Fails=== | |||

The value is roughly <math> g \approx 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} </math>. functions really effectively close to the Earth's surface, but there are certain boundaries to its applicability. | |||

'''1. Significant Changes in Altitude''' | |||

When the height of an object reaches a significant portion of Earth's radius, we start to see a noticeable decrease in the value of <math> g </math>. | |||

* At the summit of Mount Everest, the value of <math> g </math> is approximately 0.3% less than at sea level. * When you're 300 km above Earth, which is a common altitude for low-Earth orbit, the acceleration due to gravity, represented by <math> g </math>, is roughly 90% of what it is at the surface. | |||

In these situations, we need to apply the complete Newtonian formula: ::<math> g = \frac{GM}{(R_{Earth} + h)^2} </math> | |||

'''2. Variations in Local Mass''' | |||

The Earth has its imperfections and variations. The variations in gravitational strength can be attributed to differences in crust density, the presence of mountain ranges, and the formation of ocean trenches. The distinctions here play a significant role in geophysics and resource exploration, yet they tend to be too minor to influence basic physics problems. | |||

'''3. Beyond Our Planet''' | |||

The constant-g model is relevant primarily in situations where one mass is significantly larger than the others, and the distances involved are relatively small compared to the radius of the planet. Each planet and moon has its own unique value of <math> g = \frac{GM}{R^2} </math>. | |||

==Examples== | ==Examples== | ||

| Line 79: | Line 119: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Prior to the age of Newton, gravity as a force was a totally foreign concept. During the 17th century, Galileo realized that all objects, regardless of mass, fall with the same acceleration towards Earth. It was in 1687 when Newton published his ''Principia'' that he hypothesized that gravity acts as a force whose magnitude is inversely proportional to the square of distance between objects. This description was incomplete, however, and remained unfinished until Cavendish determined the value of ''G'', the universal gravitational constant. | Prior to the age of Newton, gravity as a force was a totally foreign concept. During the 17th century, Galileo realized that all objects, regardless of mass, fall with the same acceleration towards Earth. It was in 1687 when Newton published his ''Principia'' that he hypothesized that gravity acts as a force whose magnitude is inversely proportional to the square of distance between objects. This description was incomplete, however, and remained unfinished until Cavendish determined the value of ''G'', the universal gravitational constant. The purpose of this venture was to eventually determine the mass of Earth, which one he found the value of ''G'', he could determine. | ||

==Connectedness== | ==Connectedness== | ||

1.How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in? | 1.How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in? | ||

:: | :: I am personally interested in our solar system, and how the planets have orbited each other. The gravitational fields of each planet and their moons control how how solar system orbits. | ||

2. How is it connected to your major? | 2. How is it connected to your major? | ||

::As a civil engineering major, in general understanding the laws of physics ensures that the tools and construction we create are safe and realistic. | ::As a civil engineering major, in general understanding the laws of physics ensures that the tools and construction we create are safe and realistic. Research on gravitational fields has allowed civil engineers to test the bounds of construction, and also know when gravitational fields need not be considered. | ||

Is there an interesting industrial application? | |||

3. Is there an interesting industrial application? | |||

The leaning tower of Pisa is an example of civil and structural engineers using gravitational fields to their advantage. They calculated the center of mass of the tower, and the center of mass is not outside of the base, allowing it to tilt without ever falling. | |||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Latest revision as of 23:05, 2 December 2025

[[Dylan Mount – Spring 2025] This section describes gravitational force near Earth's surface, including applications and relevant derivations.

Main Idea

Close to the surface of the Earth, the acceleration caused by gravity remains roughly the same. Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation tells us that every pair of masses pulls on each other. The strength of this attraction depends on how big the masses are and how far apart they are from each other.

When we think of Earth as a point mass, we can say that an object sitting on the surface is about one Earth radius away from the center of our planet. The height of most everyday objects is so tiny compared to the vast radius of the Earth that the difference in distance is practically unnoticeable. This explains why we can consider gravitational acceleration g to be constant near the surface of the Earth.

A Mathematical Model

From Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation we know:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {F}_{grav}=G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\ }[/math]

Where

- F is the gravitational force between the masses;

- G is the gravitational constant, [math]\displaystyle{ 6.674×10^{−11} \frac{N m^2}{kg^2}\ }[/math];

- m1 is the mass of the first object;

- m2 is the mass of the second object;

- r is the distance between the objects.

Since the only forces acting on a object in free fall near earth's surface are it's weight, (mass and gravity), we can set [math]\displaystyle{ {F}_{grav} = {mg} }[/math] ,and then plug that into Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation. After canceling out the constants, we arrive at the gravitational constant for a free falling object near earth.

- [math]\displaystyle{ {g} = \frac{GM_{Earth}}{R_{Earth}^2} }[/math]

Near Earth's surface g is unchanging. As such, we define it as the gravitational constant near Earth's surface, g, which is approximately [math]\displaystyle{ 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math]. This calculation is shown below:

- [math]\displaystyle{ C= \frac{(6.67*10^{-11} \frac{m^3}{kgs})(5.972*10^{24} kg)}{(6.378*10^{6} m)^2} = 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math]

This then puts the force near Earth due to gravity into a much simpler form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{\mathbf{F}}_{grav}|= mg }[/math]

Where

- g is the near-Earth gravitational constant, as defined above to be [math]\displaystyle{ 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math]

- m is the mass of the object whose behavior we are interested in

The gravitation constant g applies to all masses significantly smaller than Earth's mass. These masses will all fall at the same acceleration.

The Gravitational Field

The gravitational field shows us how a mass affects the space that surrounds it. The strength of the field at a specific point influences the gravitational force that a mass feels when it is positioned there.

Field lines move toward the center of the Earth and become more concentrated as the strength of the field increases.

The gravitational field strength can be expressed in vector form as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec g = \frac{GM}{r^2} \hat r\ }[/math]

Conceptual Question: Say you are standing in the basement of a building and weigh yourself. Then you immediately go to the 10th floor of the same building and weigh yourself again. Is your weight the same?

- Your weight is not the same, however the significance that it changes is negligible if you are just traveling to the top of a building. Although you are further from the Earth's center of mass, the difference in distance from the Earth's center of mass is too small to significantly change your weight. Although your weight may change in varying levels due to your distance from Earth's surface, your mass will always stay the same. This is because [math]\displaystyle{ {F} = {ma} }[/math]

Common Misunderstandings About Gravity

Some common beliefs about gravity might not be as accurate as we think. Addressing these misunderstandings fosters a deeper understanding of physics and helps prevent typical errors during exams.

1. "Heavier objects tend to fall faster than those that are lighter."

This isn't true when air resistance is not a factor. Close to the surface of our planet, everything falls at the same speed, with an acceleration of [math]\displaystyle{ g = 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math], no matter how heavy or light it is. Although heavier objects feel a stronger gravitational force (as described by [math]\displaystyle{ F = mg }[/math]), they do not undergo a greater acceleration.

2. "Astronauts in orbit feel weightless." Astronauts remain firmly within the embrace of Earth's gravitational pull. They float because they are constantly falling towards Earth, which gives us that feeling of weightlessness. At typical orbital altitudes, gravity remains roughly 90% of what we experience on the surface.

3. " No matter where you are on Earth, your weight remains constant." The weight of an object is influenced by how far it is from the center of the Earth and the way mass is distributed within the Earth itself. Your weight is a bit lighter at the equator due to the Earth's larger radius in that region, while you feel a bit heavier at the poles. The variations may be slight, yet they can be quantified.

A Computational Model

Using the approximation derived above, we can create a computational model for the force of gravity near Earth's surface by applying Newton's second law in an iterative fashion to update acceleration, velocity, and finally position. This allows us to simulate the motion of an object near Earth's surface using only its mass. Seen below is a GlowScript code snippet accomplishing this iterative update technique.

- Fnet = vector(0, -g, 0)

- ball.vel = ball.vel + Fnet / ball.m * deltat

- ball.pos = ball.pos + ball.vel * deltat

When the Constant-g Assumption Fails

The value is roughly [math]\displaystyle{ g \approx 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math]. functions really effectively close to the Earth's surface, but there are certain boundaries to its applicability.

1. Significant Changes in Altitude

When the height of an object reaches a significant portion of Earth's radius, we start to see a noticeable decrease in the value of [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math].

- At the summit of Mount Everest, the value of [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is approximately 0.3% less than at sea level. * When you're 300 km above Earth, which is a common altitude for low-Earth orbit, the acceleration due to gravity, represented by [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math], is roughly 90% of what it is at the surface.

In these situations, we need to apply the complete Newtonian formula: ::[math]\displaystyle{ g = \frac{GM}{(R_{Earth} + h)^2} }[/math]

2. Variations in Local Mass The Earth has its imperfections and variations. The variations in gravitational strength can be attributed to differences in crust density, the presence of mountain ranges, and the formation of ocean trenches. The distinctions here play a significant role in geophysics and resource exploration, yet they tend to be too minor to influence basic physics problems.

3. Beyond Our Planet The constant-g model is relevant primarily in situations where one mass is significantly larger than the others, and the distances involved are relatively small compared to the radius of the planet. Each planet and moon has its own unique value of [math]\displaystyle{ g = \frac{GM}{R^2} }[/math].

Examples

Introductory

Suppose a 50 kg man stands on the Earth's surface. What is the magnitude of the gravitational force experienced by the man?

First notice that since we are near Earth's surface, it is appropriate to use our approximation of gravitational force rather than Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation. As such, recall [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{\mathbf{F}}_{grav}|= mg }[/math]. Here, m is equal to 50 kg, and g is equal to [math]\displaystyle{ 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math]. This means that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{\mathbf{F}}_{grav}|= mg = (50 kg)(9.8 \frac{m}{s^2}) = 490 N }[/math]

Intermediate

A person is laying on their back and pushing a 20 kg weight straight up (they're bench pressing the weight). What is the magnitude of the force they must be exerting on the weight if the weight is moving straight up without any acceleration?

We know from Newton's Second Law that force is directly proportional to acceleration. Thus if acceleration is zero, net force must also be zero and the weight will move at a constant velocity. This means that the force exerted by the person must be equal in magnitude to the force of gravity on the object (since they act in exactly opposite directions).

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_{g}=F_{person}=mg }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_{person}=(20 kg)(9.8 \frac{m}{s^2})=196 N }[/math]

Advanced

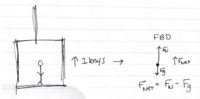

Suppose a 60 kg person is standing in an elevator that is accelerating upwards at [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math]. If they are standing on a scale, what does that scale read while the elevator accelerates upwards? A picture illustrating the situation is attached.

Here, the net acceleration is the same as that of the elevator, which is [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \frac{m}{s^2} }[/math]. The mass is 60 kg. In order to determine the weight that the scale reads, we must look at the normal force exerted by the scale.

The above means that the net force is in the upwards direction.

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{\mathbf{F}}_{net}|=F_{N}-mg=ma }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_{N}=m(a+g) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_{N}=(60 kg)(1 \frac{m}{s^2} +9.8 \frac{m}{s^2}) = 648 N }[/math]

Importance

Understanding gravity and its applications is fundamental to building intuition for our universe. On a small scale, we can use our knowledge of Earth's intrinsic qualities to simplify many basic physics problems and better understand the world around us, but the approximation scheme described here can be used for any (relatively uniform) bodies, including other planets in our solar system, extending its usefulness to beyond just Earth's surface. In particular, the ideas in this article help to show why a scale would show different values depending upon the planet on which it's placed (try calculating your weight on the moon, for instance).

From an industrial perspective, understanding gravitational force near Earth's surface is important because it may affect the design process for various products. When designing a bridge, for instance, one must verify that the force on the bridge due to gravity will not be strong enough to undermine the bridge's stability. Even when making a lamp it's important to check that a joint is powerful enough to withstand the torque experienced by the object due to the force of gravity near Earth's surface.

History

Prior to the age of Newton, gravity as a force was a totally foreign concept. During the 17th century, Galileo realized that all objects, regardless of mass, fall with the same acceleration towards Earth. It was in 1687 when Newton published his Principia that he hypothesized that gravity acts as a force whose magnitude is inversely proportional to the square of distance between objects. This description was incomplete, however, and remained unfinished until Cavendish determined the value of G, the universal gravitational constant. The purpose of this venture was to eventually determine the mass of Earth, which one he found the value of G, he could determine.

Connectedness

1.How is this topic connected to something that you are interested in?

- I am personally interested in our solar system, and how the planets have orbited each other. The gravitational fields of each planet and their moons control how how solar system orbits.

2. How is it connected to your major?

- As a civil engineering major, in general understanding the laws of physics ensures that the tools and construction we create are safe and realistic. Research on gravitational fields has allowed civil engineers to test the bounds of construction, and also know when gravitational fields need not be considered.

3. Is there an interesting industrial application? The leaning tower of Pisa is an example of civil and structural engineers using gravitational fields to their advantage. They calculated the center of mass of the tower, and the center of mass is not outside of the base, allowing it to tilt without ever falling.