Work Done By A Nonconstant Force: Difference between revisions

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

= Work Done By A Nonconstant Force = | = Work Done By A Nonconstant Force = | ||

'''Claimed by | '''Claimed by Miller Lindsley – Fall 2025''' | ||

This page explains how to calculate work done when the force applied is not constant. It includes conceptual explanations, worked examples, mathematical and computational models, and embedded simulations to make this concept easier to understand. | This page explains how to calculate work done when the force applied is not constant. It includes conceptual explanations, worked examples, mathematical and computational models, and embedded simulations to make this concept easier to understand. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

* '''Space physics''': Rockets and satellites feel variable gravity | * '''Space physics''': Rockets and satellites feel variable gravity | ||

An interesting industrial example of work done by a non-constant force is the operation of a car engine. The torque produced by an internal-combustion engine is not constant, it depends on the engine speed (RPM). As the RPM changes, the engine’s torque follows a characteristic “torque curve,” rising to a peak and then decreasing. Because the driving force on the wheels is proportional to engine torque, the force applied to the car varies continuously, making it a real-world industrial example of work done by a non-constant force. | |||

== History == | == History == | ||

| Line 104: | Line 105: | ||

=== Simulations === | === Simulations === | ||

* [https://trinket.io/glowscript/49f7c0f35f Spring-Mass Trinket Model] | * [https://trinket.io/glowscript/49f7c0f35f Spring-Mass Trinket Model] | ||

=== Refrences === | |||

* [https://ateupwithmotor.com/terms-technology-definitions/horsepower-vs-torque/\ Torque Curve Refrence] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:54, 30 November 2025

Work Done By A Nonconstant Force

Claimed by Miller Lindsley – Fall 2025

This page explains how to calculate work done when the force applied is not constant. It includes conceptual explanations, worked examples, mathematical and computational models, and embedded simulations to make this concept easier to understand.

The Main Idea

Before we understand nonconstant force, let's review constant force.

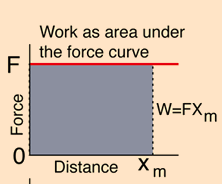

For constant force:

- Work = Force × Distance

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = F \cdot d }[/math]

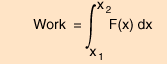

In real-life, however, forces often vary over distance. In that case, we use:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = \int_{x_1}^{x_2} F(x) \, dx }[/math]

This integral calculates the total work as the area under the curve on a Force vs. Distance graph.

Mathematical Model

Work done by a varying force is found by breaking the motion into tiny intervals:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = \sum \vec{F}_i \cdot \Delta \vec{r}_i }[/math]

As the interval becomes very small, it becomes a definite integral:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = \int \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} }[/math]

Spring Example

If [math]\displaystyle{ F = kx }[/math], we derive:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = \int_0^x kx \, dx = \frac{1}{2}kx^2 }[/math]

Computational Model

Computational models can approximate work using many tiny time steps. Below is Python code modeling a vertical spring in VPython:

<syntaxhighlight lang="python">

- initialize conditions

L = ball.pos - spring.pos

Lhat = norm(L)

s = mag(L) - L0

Fspring = -(ks * s) * Lhat

- momentum principle

ball.p = ball.p + (Fspring + Fgravity) * deltat </syntaxhighlight>

Interactive Model

Try out this Trinket simulation of spring motion: View the simulation on Trinket

Examples

Simple

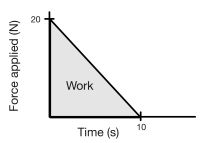

Question: A person pushes a box and slowly loses strength after ten seconds. It can be described using this formula: F(x) = 20 - 2x. How much work was applied to the box? Solution:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = 1/2 \cdot 10 \cdot 20 = 100 \, J }[/math]

Middling

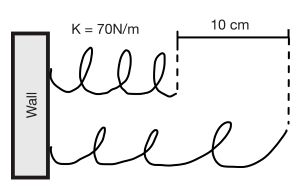

Question: A spring with [math]\displaystyle{ k = 70 \, N/m }[/math] is stretched 10 cm.

Solution:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = \frac{1}{2} k x^2 = \frac{1}{2}(70)(0.1)^2 = 0.35 \, J }[/math]

Difficult

Question: How much work is done by Earth’s gravity on an asteroid falling from distance [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] to radius [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math]?

Solution: Start with Newton’s law of gravitation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F = \frac{GMm}{r^2} }[/math]

Then integrate:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W = \int_R^d \frac{GMm}{r^2} \, dr = GMm \left( \frac{1}{R} - \frac{1}{d} \right) }[/math]

Connectedness

Understanding work by nonconstant forces is key in many fields:

- Springs: Used in trampolines, shock absorbers, and mechanical pens

- Engineering: Fluid tanks fill unevenly, requiring nonconstant work

- Energy: Hydroelectric turbines rely on variable water flow

- Space physics: Rockets and satellites feel variable gravity

An interesting industrial example of work done by a non-constant force is the operation of a car engine. The torque produced by an internal-combustion engine is not constant, it depends on the engine speed (RPM). As the RPM changes, the engine’s torque follows a characteristic “torque curve,” rising to a peak and then decreasing. Because the driving force on the wheels is proportional to engine torque, the force applied to the car varies continuously, making it a real-world industrial example of work done by a non-constant force.

History

Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis was the first to define "work" as force over distance. Later physicists used calculus to model work by nonconstant forces.

Further Reading & External Links

Book

- Chabay & Sherwood – Matter and Interactions (4th ed.)